We Underestimate the Kids of Working Moms, and Other Interesting New Research

Posting is for Jerks; The Upsides of a WFH Spouse; Working Mom Bias & Child Penalties; The Mental Toll of Unemployment (for Men); Covid & the Parental Happiness Gap; The Privilege of Partnership

Hello Everyone!

In under the wire here, but this newsletter is technically on time (never said it would be in your inbox first thing). This is a long one so I’m going to skip the pleasantries and get right into the research. Sorry in advance for the typos!

Posting is for Jerks

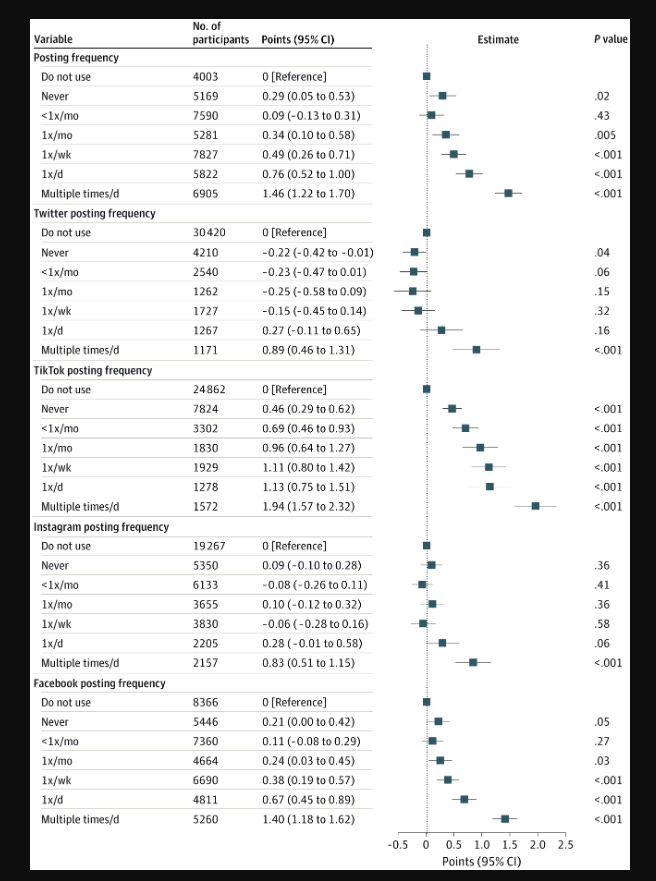

Maybe this finding won’t come as a surprise to many people, but it turns out that there is a pretty strong association between social media use (especially posting) and irritability. Those who use social media for “most of the day”—about a quarter of the sample—are a particularly irritable bunch. The relationship holds across multiple platforms including Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok, and even after accounting for depression and anxiety. When it comes to posting in particular, the authors found a dose-dependent association—the more you post, the more irritable you are—across all platforms (Instagram posting isn’t quite as bad). These are associations, of course, so we don’t know if it’s that irritable people like to post or if posting makes you irritable, but it’s sort of funny either way.

The Upsides of a WFH Spouse

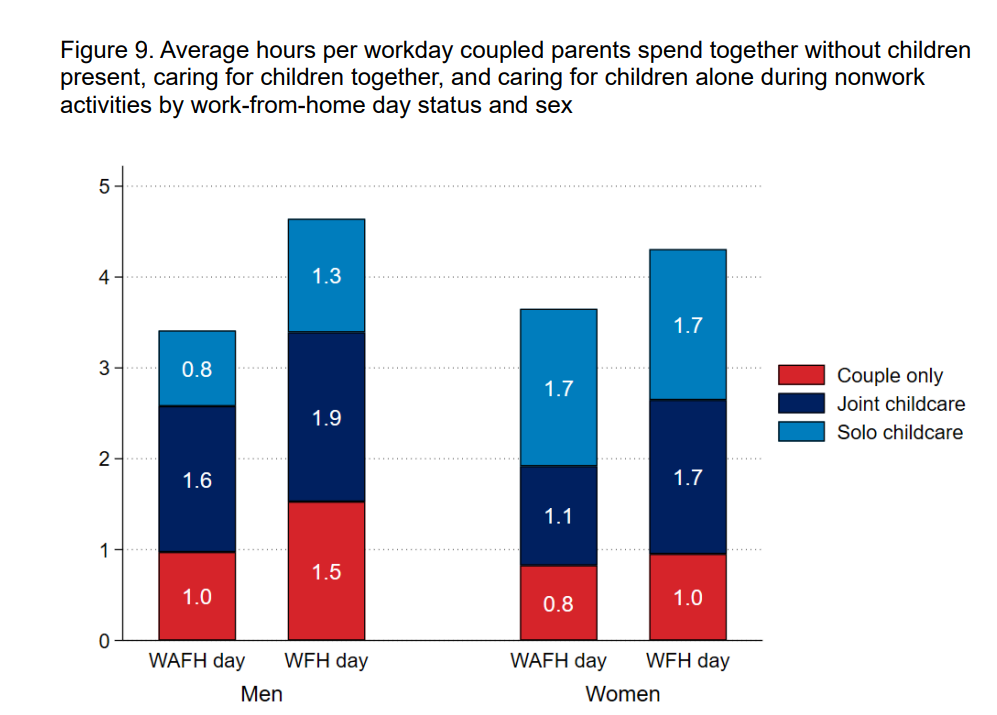

I’m sharing two new pieces of research here. The purpose of the first study was to figure out partner work location influences work hours among couples. They find that, compared to onsite work, both partners switching to a hybrid arrangement leads to a 5.4% bump in their collective work hours. Both partners switching to fully remote leads to a 3.2% decrease in work hours. The joint hybrid working schedule leads to an even bigger bump in working hours among fathers (6.2%) and mothers (9.4%) of young children. And the dip in work hours among couples working fully remote isn’t quite as steep among mothers and fathers of young kids. For the authors, I think the main takeaway is that hybrid working arrangements are better for improving women’s position in the labor market, but I found some of their supplementary analysis in some ways more interesting (see chart below).

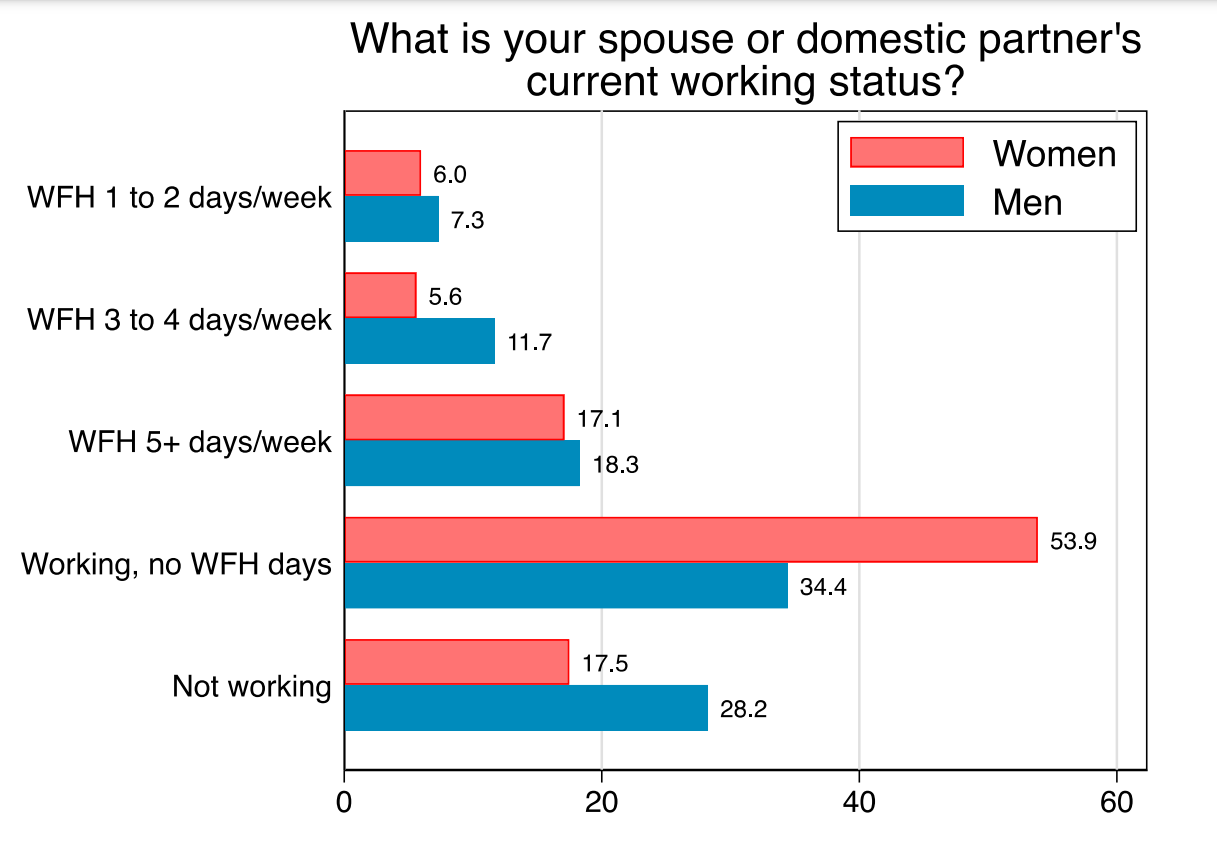

On WFH days, both mothers and fathers spend more time alone together, and more time doing joint childcare. And then for fathers, WFH leads to them spending more time doing solo childcare. All of that sounds kinda nice to me, frankly, regardless of whether it is translating to more working hours for either party. In other words, there is some value, I think, in having a work from home spouse. Which brings me to the next bit of research. The fact that women are more likely to work from home in general means they are less likely to reap the benefits of having a work from home spouse. According to a recent update from WFH Research, women are far more likely than men to have a spouse that works out of the home five days a week (raises hand). Over half of women do, while about a third of men do.

We Underestimate the Kids of Working Moms

Buckle up, this is sort of a complex one. As I’ve mentioned in a previous newsletter, women’s earnings tend to take a hit following the birth of a child while fathers’ don’t. An interesting aspect of the literature on this so-called “child penalty” is that it has proven very, very hard to meaningfully reduce. One possible explanation for the persistence of the child penalty is that perhaps women’s earning potential is lower than men’s, such that when push comes to shove, it makes more sense for them to reduce their working hours. Another holds that it has more to do with the belief that women have an “absolute advantage” over men in childrearing i.e. they are just better at it than men are. If this is the case, then even if women had equal earning potential to men, they will end up leaving the labor market at higher rates than men to care for their kids.

This UK-based paper explored the “absolute advantage” theory by investigating people’s perceptions of how full-time working motherhood impacts kids (as measured by their likelihood of graduating from university and their earnings at 30). And indeed, the authors find that, on average, “people expect worse outcomes for children when mothers work long hours relative to fathers.” There was quite a bit of variation in these beliefs due to the respondent’s personal background. Consistent with some other research on the subject, people who grew up with full-time working moms didn’t share the belief that working motherhood harms kids. Meanwhile, the idea that full-time maternal work harms kids was strongest among women who themselves experienced the biggest post-birth employment penalties. This confirms the idea that people’s decisions about work post-motherhood have a lot to do with their beliefs rather than just their earning potential. Probing into the nature of these beliefs, the authors found that it basically comes down to expectations about how mothers and fathers will spend their free time: “with equivalent time mothers will spend more time on skill investments with children than will fathers.”

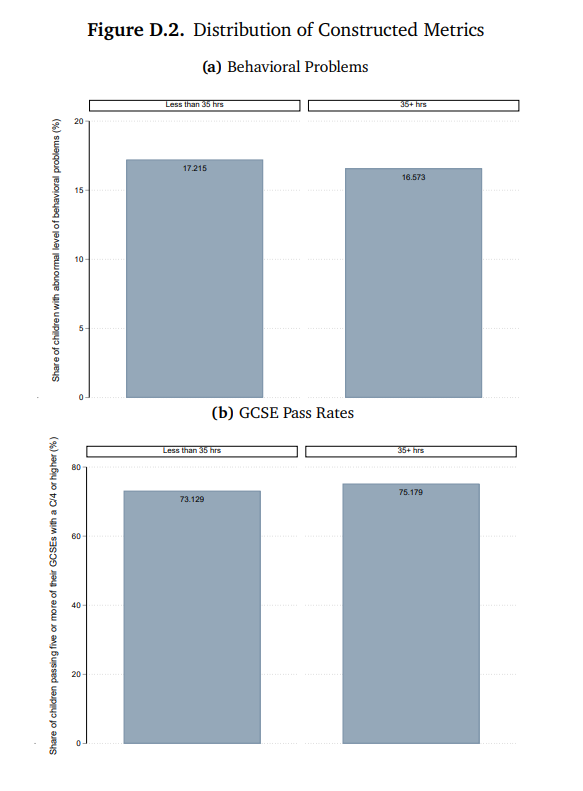

The authors then presented the respondents with some actual data about how kids in different maternal work arrangements fare on their GCSEs (a set of exams given to teens here in the UK). Comparing kids of mothers who worked part-time to those who worked full-time (and holding familial education and income constant), they find little difference in the pass-rate (73% for part-time working moms versus 75% for full-time working moms). They find that respondents tend to underestimate how well children of full-time mothers actually do. And when they are presented with accurate information, those who under-estimated the kids of full-time working moms actually do update their beliefs and lower their expectations of harm from working motherhood.

The Connection Between Working Mom Bias and Child Penalties

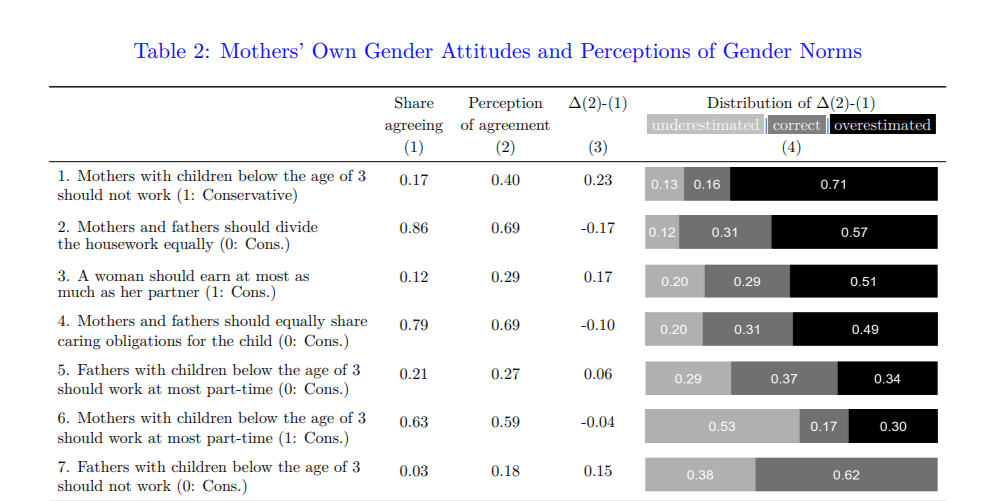

In a similar vein as the study above, this one, based in Germany, explores working mom norms from a slightly different angle. Interestingly, the authors find that there is a pretty big gap between mothers’ perceptions of gender norms in their city and actual norms, especially when it comes to norms about moms working. So for example, only 17% of mothers surveyed agreed with the statement that “Mothers with children below the age of 3 should not work,” but the average surveyed mother thought that 40% of other mothers would agree with it. All told, “71% of mothers perceive the norm in their city as more conservative than it actually is,” the authors write.

Interestingly, presenting mothers with accurate information about norms actually makes moms a bit more liberal, i.e. lowering the likelihood that they agree with that mothers with kids under three shouldn’t work. The corrected info about actual norms also influenced the mother’s stated plans to return to work, increasing the likelihood that they plan to increase their working hours. In other words, “providing accurate information about prevailing gender norms regarding maternal employment not only affect mothers’ perceptions of gender norms, but also shapes their own gender attitudes and labor-supply expectations.” So moms were less likely to frown upon working mothers, and more likely to plan on working themselves, when they realized other people weren’t that judgey about it. Norms, and our perception of them, are pretty powerful!

The Mental Toll of Being an Unemployed Man

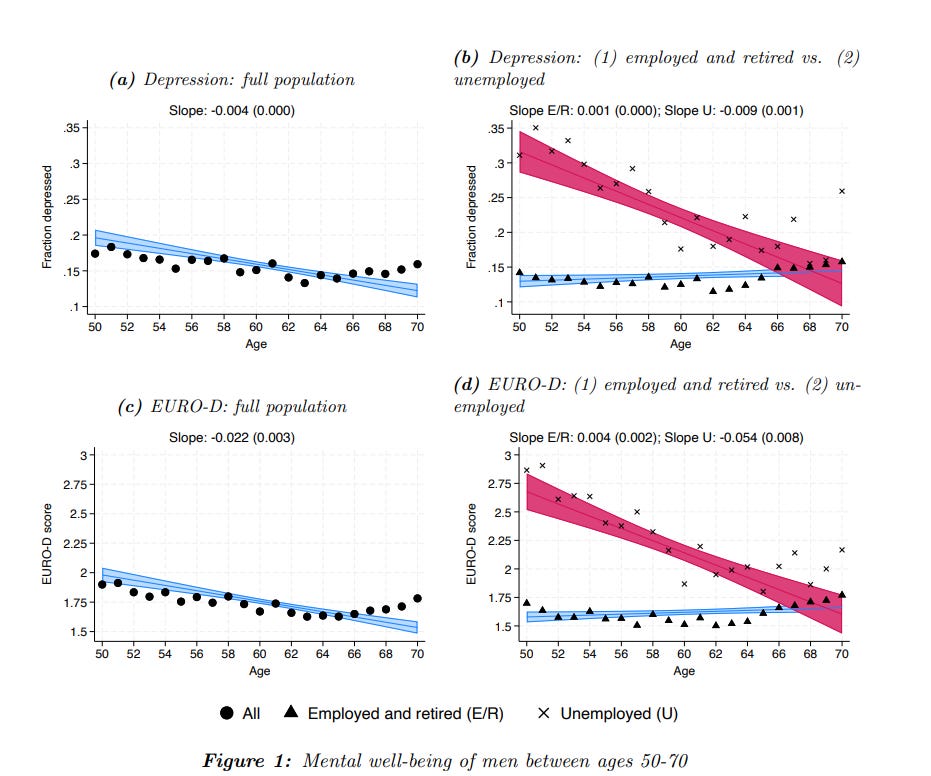

Speaking of the power of social norms, this study found that the expectation that adults work has a pretty powerful negative impact on the mental well-being of middle-aged unemployed men. So much so that as their peers age and start retiring and the social pressure to work weakens, the mental well-being among unemployed men actually improves.

How Covid Influenced the Parental Happiness Gap

The background here is that for a while, parents tended to report lower levels of well-being than nonparents, but in more recent years, some evidence suggests that this “parental wellbeing gap” has narrowed and even closed entirely. This study looked into whether the parental happiness gap re-emerged during Covid. They end up confirming that by 2018, the parental happiness gap had indeed closed but re-emerged in 2021–with parents faring better than nonparents. This was driven by the fact that while happiness fell for both parents and nonparents, it fell more for the latter. The authors suggest that perhaps parenthood essentially “buffered” the well-being of parents against the loneliness and isolation brought on by the pandemic.

That said, breaking it out by gender, the authors found that fathers were happier than nonfathers during the pandemic, but the same was not true of mothers, “who had similar levels of happiness as non-mothers in both 2018 and 2021.” So kids functioned as a better buffer against isolation for dads than moms. Looking at education, they found that while in 2018, higher educated parents had a happiness advantage over their highly educated non-parent peers, this gap didn’t exist during the pandemic, (which I think is consistent with work by Brad Wilcox and Wendy Wang, who found that while poorer moms consistently report lower levels of life satisfaction than richer moms, the richer moms had a bigger decline in life satisfaction during the pandemic). Meanwhile among the lower educated, if I’m understanding correctly, there wasn’t a happiness gap between parents and nonparents in 2018, but because declines in happiness steeper among the latter, a parenthood-happiness advantage emerged among the lower educated during the pandemic. So, basically, the pandemic led to a shrinking of the parental happiness advantage among the highly educated and to an emergence of one among the less educated.

The Privilege of Partnership

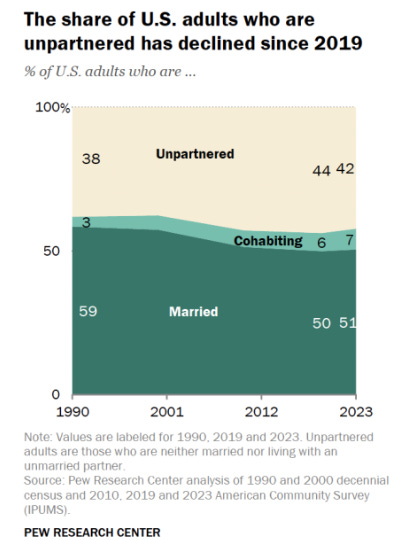

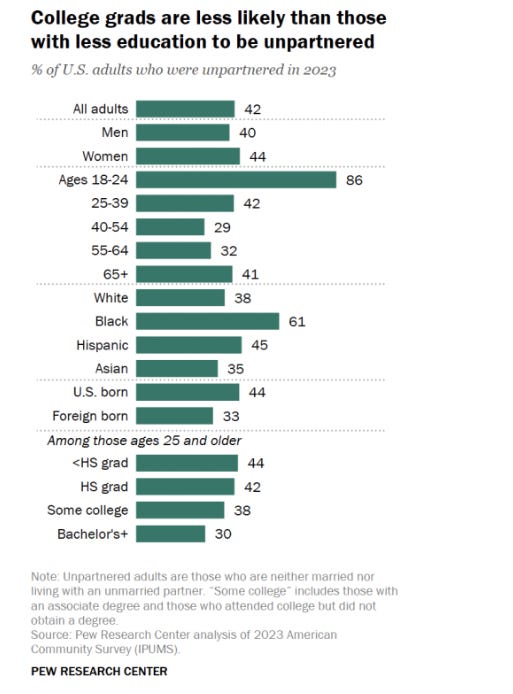

Not going to go deep on this one, but a fresh Pew survey found that the share of Americans that are unpartnered, which has generally been growing in recent decades has plateaued and even declined in recent years. They break it out across a variety of metrics. The one that stood out to me, and that fits with other research I’ve shared in this newsletter, is that there is a very clear relationship between education and one’s likelihood of being unpartnered: “44% of adults ages 25 and older without a high school diploma are unpartnered, whereas 30% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree are.” Partnership is a privilege!

One thing to consider anytime effects on children are discussed is - what effects on children are being considered, measured, and analyzed. Social-emotional? Academic? Marriage? Satisfaction? Work status? Type of work status? I find that working decisions are really complex and can't really be parsed out in a randomized control trial. The confounding variables are astounding .. What are the demands of each job? What family support do they have? How satisfied are they with the child care offerings? What is the family income for 1 full time income vs 2 or 1.5? What are their personal, professional and family priorities? How much do their decisions feel freely made, versus coerced by circumstance? I love the WFH research - and you can see how much that could influence a family's choices and satisfaction with those choices. As someone in the trenches, we need more supports, leaves, part-time arrangements for families, big investments in children, and more flexible educational systems. Solidarity to all navigating this!

I’d love to read (and will ask a librarian friend if she’s heard of) a study or report that rounded up all the outcomes from family/work studies and looked at what was most common - lifetime earnings? wages at 30? graduating high school/college/equivalent? It seems like benefits of a wide variety of early interventions “fade out” (Head Start academic gains fade away, a baby of a SAHP may experience fewer infant infections but have the same level of health at 3rd grade, etc). I also wonder at how parents desires line up with measured outcomes - do a large number of moms stay home (or seek employment) with an eye to long term academic/behavioral outcomes or in response to more immediate concerns like preferring care to employment, quality/availability of child care, etc