How Americans Feel About "Staying Together for the Kids," and Other Interesting New Research

Refusing to have kids with your spouse, the decline of hanging out in the street, giving thanks at Thanksgiving Dinner (and why my British friends think that's weird).

Hello Everyone,

Welcome to my first round-up! After I published my launch post, I started worrying that perhaps there would be no interesting research to cover this week, which would be extremely awkward! But if there is one thing I’ve learned over the past few years, it is that there is literally always interesting research being published. This week was no different. We’ve got some survey data about how Americans feel about “staying together for the kids,” and whether people think it’s okay for a married person to refuse to have a kid with their spouse. Other topics include: the decline of socialising on urban streets, the skills you build while homemaking (!?!), and what happens when you invite a Brit to Thanksgiving.

Should you stay together (or marry) for the kids? Americans won’t judge either way.

This study surveyed Americans to see if they agree that “Couples who have children should get married,” and “People should try to stay married for the sake of their children.” Turns out only 16% of Americans agree with both statements. The majority (55%) did not agree with either—in other words, they think it’s okay to forgo marriage or get divorced even if there are kids in the picture. Another 22% say couples with kids should really get married, but that it’s okay for parents to divorce. Why is this interesting? Well, it’s one more data point suggesting that attitudes toward marriage have shifted over time. Sometimes people conclude from this data that Americans just don’t value marriage anymore, and I remain skeptical that’s really what’s going on. But there’s no doubt that Americans have gotten more skittish about weighing in on whether or not someone else ought to get or stay married.

Is it okay to refuse to have kids with your spouse?

If you were to try and guess whether women or men are more likely to say that it’s wrong for a married person to refuse to have a child with their spouse, what would you say? Well, this study has the answer. The vast majority of respondents (72.8%), whether men or women, say it’s okay for either spouse to refuse to have a child. But a sizeable proportion (22%) say it’s unacceptable for either to do so—and women are considerably more likely to fall into this camp.

I can’t actually tell if I’m surprised by that (I didn’t make a guess prior to reading the study, unfortunately). I might have assumed that, given the physical toll of pregnancy and the fact that women do more of the actual work of child rearing, women would be more on board with refusal. Then again, maybe women attach more personal significance and meaning to having kids and thus find it more unthinkable to refuse someone the opportunity. No clue! Would love to hear others’ thoughts on this.

Maybe homemakers have skills, too.

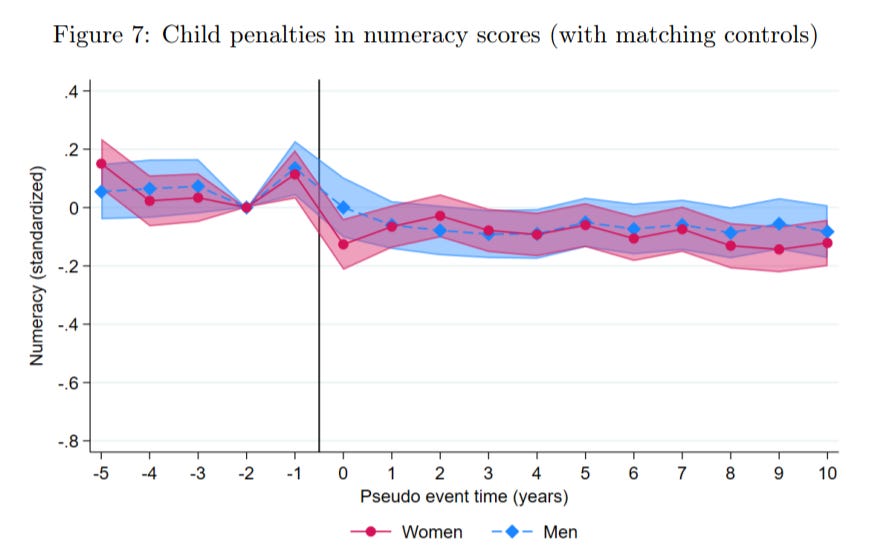

Just in case anyone out there doesn’t know: women tend to experience a persistent drop in earnings after they have a kid. The same is not typically true of fathers. The tendency for mothers’ income to dip relative to fathers’ following the birth of a child is sometimes referred to as the “child penalty.” In this working paper, the authors tested the theory that one driver of this gendered penalty is that women’s “labour market skills” erode during their longer employment interruptions. Funnily enough, the authors found a persistent drop in numeracy skills following the arrival of a baby for both moms AND dads, though it largely disappears when you control for education, as does any gap between the genders. In other words, women’s numeracy skills don’t appear to disproportionately tank after having a kid.

On its face, this might seem a bit strange because moms do in fact take longer career breaks than dads. One explanation that the authors offer is that, well, moms actually use numeracy skills in their work at home. As someone who's been banging on about the weird assumption that all your job relevant skills necessarily erode when you shift from paid employment into domestic production, I was delighted to see it challenged in an academic publication.

Shared custody is good, but tough for teens

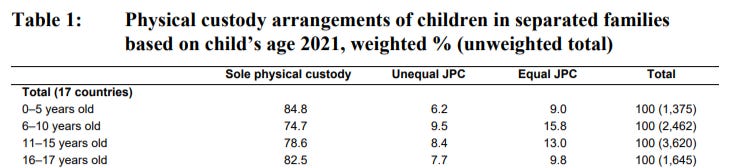

Over the past few decades, a rising share of divorced or separated couples have opted to share custody of their kids. This is good! Broadly, research finds that kids seem to fare better in a shared arrangement than in a sole custody scenario (*insert caveat about it being very difficult to establish causality on this matter*). This study adds to that body of research, finding that while kids with separated parents were overall less likely to get along with both of their parents than other kids, parent-child relationship quality among children in shared custody arrangements didn’t differ much from those in two-parent households. The one exception was older teens (14-18 yo) in shared arrangements, who were less likely to say they get along with both parents than their two-parent-household peers.

The teen exception here matches with something I found while reporting this piece about the rise of the two-household child: when you look at how custody arrangements vary by age, shared care arrangements peak in middle childhood (6-10) before steadily dropping off in the teen years. It’s hard to say exactly why, but one of the researchers I spoke to suggested that teens might find it really aggravating to switch households if it disrupts their ability to socialize with friends.

The decline of streets as social spaces

I’m sort of obsessed with how car dominance has altered the fabric of social life (and by extension childhood), so I was surprised and delighted to see this study in which the authors analysed trends in pedestrian behavior in urban public spaces (i.e. the street) in various American cities (NY, Boston, Philly) over the course of 30 years. The basic takeaways are that people are walking faster, lingering much less, and while there’s been little change in the share of people walking on their own, group interactions on the street have declined. “Urban residents increasingly view streets as thoroughfares rather than as social spaces,” the authors conclude.

This aligns with a piece I wrote over the summer about the decline of children’s street play. And to be honest, I don’t think it will come as a surprise to many youngish people. In fact, I think it surprises a lot of young people to hear that the modern understanding of streets—as places primarily serving “mobile” purposes—is actually quite strange. Streets used to serve all sorts of “stationary” functions, such as play and socializing. There’s been all this chatter about the decline of so-called “third places,” but the street was a third place!

Tough times make for Trads

Pretty straightforward. When times get tough (i.e. when unemployment rises), more people tend to adopt conservative views on gender roles in the labor market (that is, they are more likely to agree with statements like: “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.”) The relationship is, perhaps unsurprisingly, stronger in less gender equal countries with lower rates of female employment. Unfortunately, I don’t think this can explain the #tradwife phenomenon, because unemployment in America has been pretty low for a while now.

The most American (and apparently least British) tradition

Since it’s Thanksgiving week, I’ll end with this little tidbit I found tucked into a recent Pew round-up: 69% of Americans share things that they are thankful for around the Thanksgiving dinner table. That’s more than those who say a prayer or blessing (65%)! This stat stood out to me because I live in the United Kingdom and last year, my husband and I invited some British friends over to show them a proper Thanksgiving dinner. At some point, we, like good Americans, started going around the table sharing what we were thankful for—and to our surprise and dismay, it made our British guests a bit uncomfortable! We’re quite close with them so no one was offended, but they found the tradition just kinda off-putting. When we asked why, they said that at a British gathering, you probably wouldn’t go around the table and have everyone talk about themselves—if you were going to toast to something, it would be, like, the Queen or some other more unifying, less personal thing. Anyway, it tracks with other complaints I’ve heard about Americans: we just talk about ourselves too much.

It’s weird that they consider thanking someone else as talking about yourself. To me it was always a part of the holiday that was focused on other people. Often people were specifically thanking other people around the table.

It takes some conscious and/or serendipitous design elements to make streets into places. People feeling safe and welcome to transit a thoroughfare is a minimal starting point, not a successful conclusion.

www.iwritewordsgood.com/apl/patterns/apl124.htm