Why People Raised in Religious Families Volunteer So Much, and Other Interesting New Research

The Paradoxical Loneliness of the Elderly Poor; Which Kids Get to Sleep At Night (and Why); Is Independence Still A Privilege?; The 9/11 Effect (for Marriage); The Housework Reporting Gap

Hello everyone,

Every time I start drafting the opening to this newsletter, I search my brain for something funny or interesting about my life to share with you all. Unfortunately, the thing that usually comes to mind is “I’m tired.” Which isn’t funny or interesting. And then the next thing that pops into my head is typically something about my kids (5yo lost a tooth yesterday) or being pregnant (we’re finding out the gender later this week), and that stuff is probably mostly funny and interesting to me. Swatting those options out of the way, all I’ve got is that…I’m excited to head back to the U.S. later this week to visit family for the holidays? (On that note, I have an essay coming out on Sunday (the 22nd) that is sort of a festive ode to growing up with a bunch of siblings, and I’m very proud of it, so look out for it in The Atlantic if interested! I’ll be sharing a gift link on Twitter and Substack).

Anyway, I’m gonna work on this. Let me know if there’s anything in particular that you’d like to see (or like not to see) at the top of these round-ups. For now, let’s turn to the research.

Why Religious People Volunteer So Much

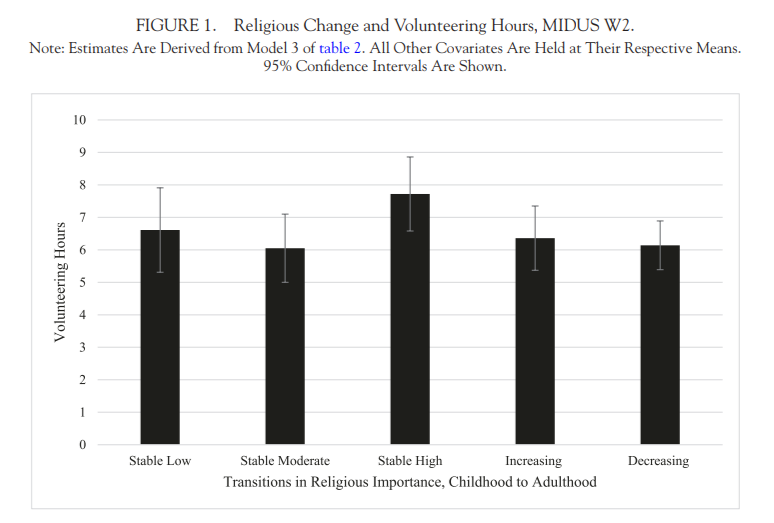

One challenge for our secularizing society is that America relies to a great extent on the labor of volunteers to run the charitable services and programs that both serve and bind communities—and religious folks do more volunteering than anyone else. In other words, the Great Dechurching is threatening our volunteer labor supply. But how important is actual religious belief in the relationship between religiosity and volunteering? Theoretically, one could imagine that it’s not religion that drives volunteering per se, but the habits that children form growing up in religious families. This study asks: “Does being raised in a religious way set into motion volunteering habits that carry on—even if the person is not religious as an adult? Or does this association depend on continued religiosity?” Spoiler alert: it’s the latter.

While it’s true that religion in childhood is associated with more volunteering in adulthood, the relationship hinges on the continued salience of religion in the adults’ lives. The volunteering habits of kids who grow up religious but whose faith lapses in adulthood are pretty much indistinguishable from those who were never religious in the first place. That doesn’t mean that being raised religious has no impact: religious adults who were raised religious do more volunteering than those for whom religion became less important OR more important over time. So a cradle Christian who hangs onto their faith as an adult volunteers more, on average, than someone who found their way to God later in life.

The Paradoxical Loneliness of the Elderly Poor

If you read the newsletter last week, you’ll remember that I included some data on what I called the “kin-poor rich.” In America and elsewhere, richer old folks tend to have not only fewer descendants than the poor (though they are more likely to have a living partner), but fewer kin overall. I think a part of me wanted to conclude from that finding that the poor have something that the wealthy lack—that they make up in the comfort of family some of what they lack in material abundance. So I was a little saddened by the results of this study that examined loneliness and social isolation among older US adults. The study was primarily focused on figuring out how these metrics were affected by the pandemic: unsurprisingly, they found that loneliness and social isolation increased during Covid but have largely returned to pre-pandemic levels since. But when they looked at how loneliness and social isolation among the American elderly varied by socioeconomic status, they found that those with lower incomes and less education reliably struggled more with both. It’s tempting to believe that financial success comes at the cost of isolation. This study suggests that perhaps that isn’t true.

Which Kids Get to Sleep At Night (and Why)

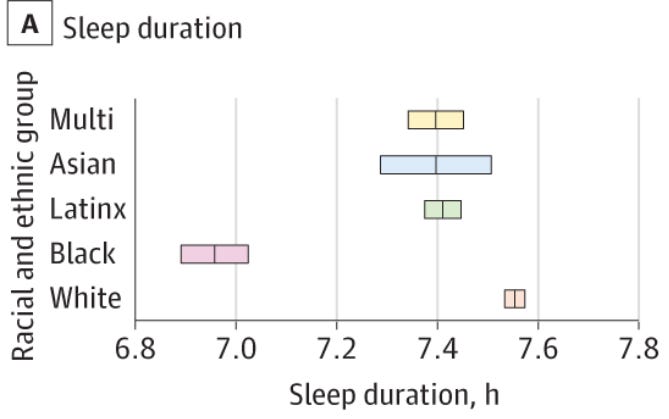

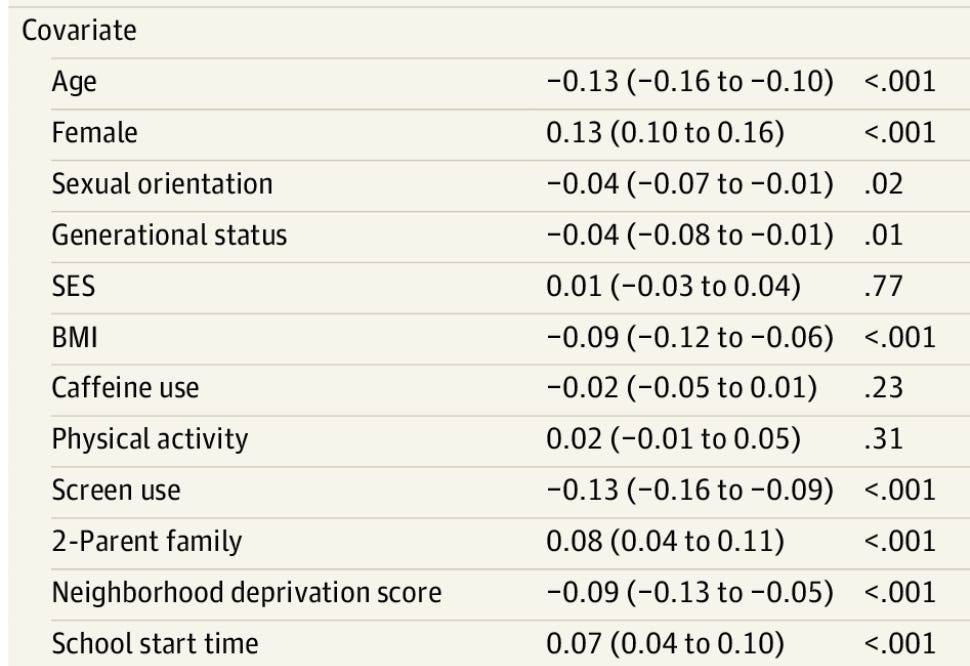

It feels silly to say this but: sleep is important, for everyone, but definitely for kids. The aim of this study was to figure out if and how the duration, quality, and consistency of kids’ sleep varies among children with different racial and ethnic backgrounds. The main finding is that, compared to their white peers, “Black, Latinx, and multiracial children consistently exhibited shorter sleep duration and later bedtime, as well as greater variability in bedtime and risetime.” Black children in particular are struggling to get good sleep.

The authors also explored how a bunch of other variables interact with kids’ sleep, with some enlightening findings. “Neighborhood deprivation,” an index that captures things like the education, employment, income, housing, and poverty level in a neighborhood, had a sizeable negative impact on sleep duration (curiously, socioeconomic status didn’t). Being in a two-parent family had a sizable positive impact. But the variable that harmed sleep duration the most (other than things like race, age, and sex) was screentime. Related: a freshly published Pew survey found for the third year in a row that just under half of teens in the U.S. are online “almost constantly.”

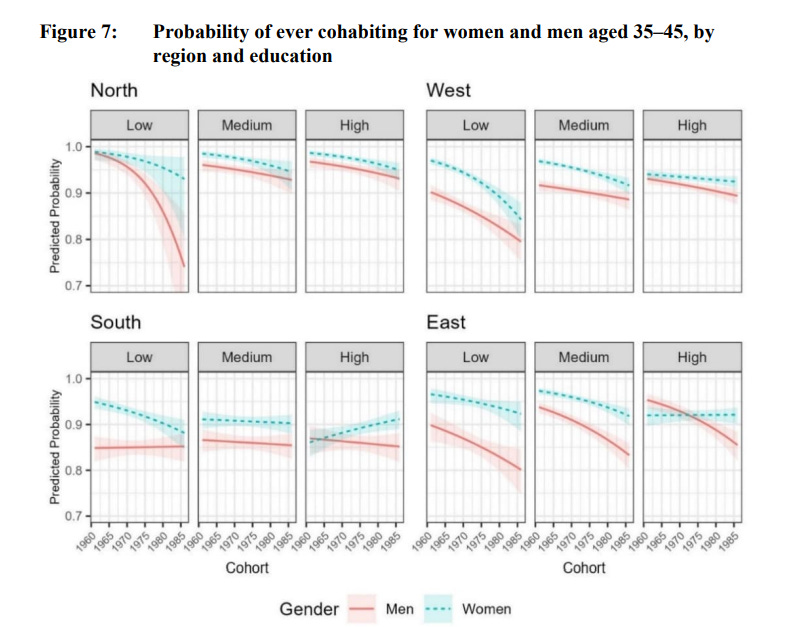

Is Independence Still A Privilege?

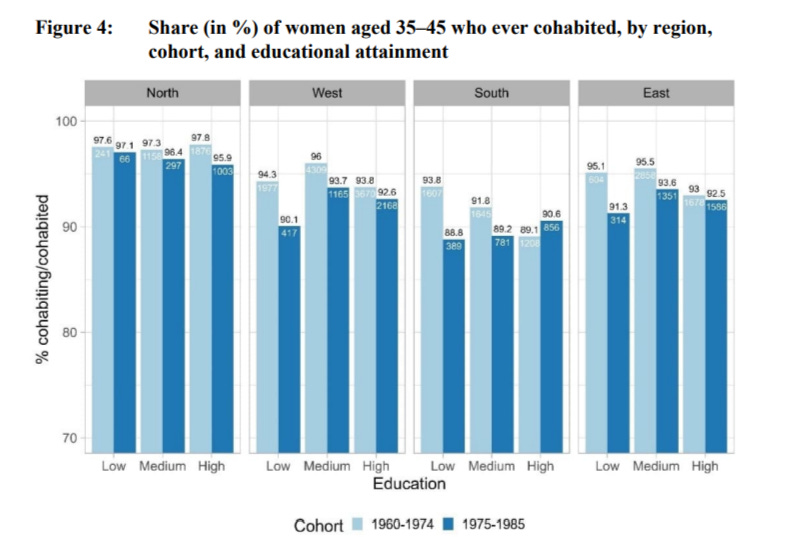

A thing that is happening that a lot of people seem unaware of is that the relationship between socioeconomic status and family formation is shifting (for women, anyway). People often point out that it’s the women with the most education and income that have the fewest kids, but as I’ve reported elsewhere, that relationship is weakening and even reversing in much of the world. This study looked at the relationship between women’s education and partnership formation in Europe and found a similar shift. Across Europe, the likelihood of ever entering a cohabiting union of any sort (married or unmarried) has dropped off more steeply among women with the least education than among those with more.

In some places, like Southern Europe, the trends are actually moving in entirely different directions: while women with little education are partnering up less, highly educated women are partnering up more than in the past. There, the relationship between partnership formation and education has actually fully reversed: women with the least education are the least likely to ever live with a partner. Meanwhile, the positive relationship between education and partnership for men is getting even stronger—look at the trend for men in Northern Europe (above)! Huge drop-off in partnership for men with the least education. Anyway, independence is starting to look less like a privilege of the rich and more like a burden of the poor.

The 9/11 Effect (for Marriage)

This one is a little random, I guess, but the author looked into whether 9/11 affected inter-ethnic marriage in the U.S. and, well, it did. Muslim intermarriage rates dropped 8 percentage points. The drop-off in Muslim marriage with white Americans was particularly steep, falling by 11 percentage points. Interestingly, those who carried on intermarrying in the post-9/11 world tended to have lower levels of education than those who intermarried prior. So it was primarily a retreat from Muslim intermarriage among the well-educated.

From the backlog:

(A housekeeping note: While I was hemming and hawing about whether or not I should start this newsletter, or simply stop obsessively following research on family dynamics, I fell behind on the research notifications in my inbox. Now that I’ve chosen the newsletter route, I am trying to zero out that backlog. A central aim of this newsletter is to share research in a timely fashion, but in order to motivate me to actually work through this backlog, I’m allowing myself to share anything that seems particularly interesting.)

The Housework Reporting Gap

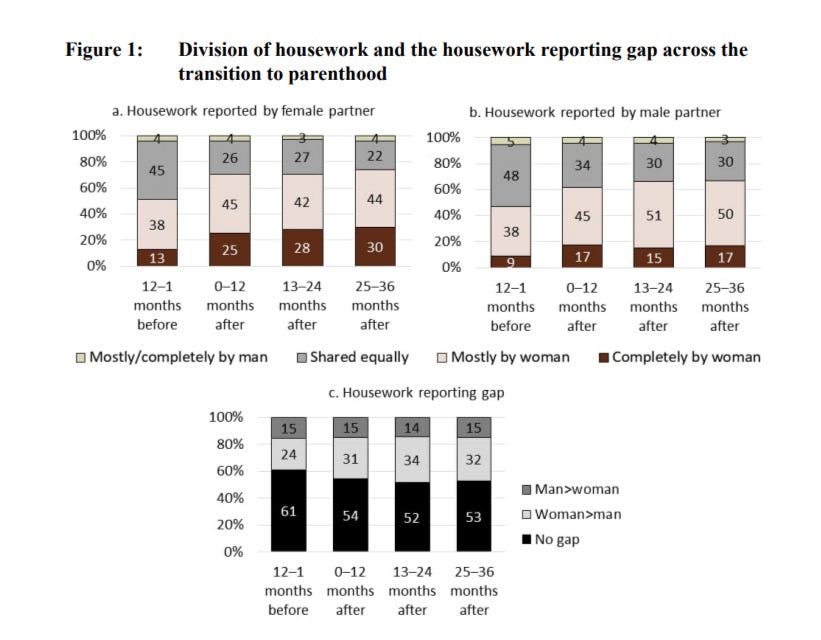

Everybody knows about the housework gap—that is, in heterosexual relationships, women tend to take on more childcare and housework than their male partners. Fewer people, perhaps, know that there is a housework reporting gap—that is, that couples often disagree on how much each partner is contributing to childcare and housework. This German-based study that examined reported housework and childcare divisions among couples before and after having a child found that such reporting gaps are not only substantial, but that they follow some interesting patterns.

First, especially when it comes to housework, it’s more common for a reporting gap to result because a women says she is doing a greater share of the housework than her husband credits her for. But it does occasionally go the other way, with men giving their wives more credit than even she herself claims. Second, both the housework gap and the housework reporting gap seem to grow over the transition to parenthood. For example, in the year leading up to birth, 13% of women said they do all the housework, and 9% of men say their wives do all the housework. By the time we get to the child’s third year of life, fully 30% of women report doing all the housework, while just 17% of men agree with that assessment. When it comes to childcare, by contrast, the share of both women and men who say the woman is doing all of it actually shrinks over time, and the likelihood of there being a reporting gap on that point is smaller in the third year than the first. And finally, reporting gaps varied by education level: couples in which both partners are highly educated have the smallest reporting gaps.

Time use and housework! I love time use. When it comes to paid work, people generally (and some subgroups more than others) overreport paid work in point-in-time estimates versus time diary measurements, but I don’t know of similar research comparing single question estimates for housework or childcare versus time diaries. I also think it would be harder to estimate, whereas most wage earners have a clearer idea of when they clock in and out versus exactly how long it takes them to cook dinner.

Personally, I find quite funny your descriptions of wooing ChatGPT into doing your bidding, and its reluctance.

The volunteer info reminds me of a conversation I had with a man who ran a soup kitchen in Fresno, CA. He said what’s most frustrating about his job is that at the winter holidays church and civic groups are on waiting lists to get their chance to volunteer, but the rest of the year he’s calling churches and clubs begging for help.