More Evidence the Economics of Fertility is Changing (for Women), and Other Interesting New Research

The Raise You’ll Need to Raise a Child; “Everything is Terrible But I’m Fine,” But for Teens and Social Media; Gaining Affluence Often Means Losing “the Village” + more.

Hello everyone,

I’m running so late today. No time for small talk!! But tons of interesting stuff to cover this week. I’m sure there are tons of typos in here that I will just have to fix later, so apologies in advance.

The Raise You’ll Need to Raise a Child

How much does it cost to raise a child in America? This paper investigates that question using an “equivalence scale,” to calculate “how much the income of a two-adult, one-child household should increase to maintain the same level of life satisfaction as a two-adult household.” The answer is somewhere between 18 and 22%, evidently. Apparently that about matches the US Census Bureau’s estimate, but is lower than the one set by the HHS poverty guidelines (26%). As such, the authors conclude that the eligibility threshold for social welfare programs in the U.S. is actually too high.

According to the authors, the reason for the discrepancy between their estimate and the one used in the HHS poverty guidelines is that the latter do not distinguish between adults and children when it comes to the cost of an additional household member, “even though supporting a child is generally less costly than supporting an adult.” With the caveat that I am not qualified to assess the merits of their findings, that statement gets a big ol’ side-eye from me. It’s the sort of thing you say when you totally ignore the cost of unpaid domestic labor and the value of having someone around to do it. Let’s say you make $50,000 a year and have to add an unemployed “dependent” to your home: would it be “less costly” to add a newborn baby to your home than a stay-at-home spouse? Both aren’t earning an income and, like everyone, cost money to clothe and feed. But only one can fold laundry and cook meals. The other needs round-the-clock, hands-on care, whether you are paying for it or not.

Highly Educated Women Have Larger “Fertility Gaps”

In both Europe and America, people are raising fewer kids than they intend. This study tried to figure out how education and relationship patterns contribute to this “fertility gap.” Analyzing data from women born in the Netherlands, between 1974 and 1984, they find that most women achieved their intended family size, though outcomes vary by education: 78% of women with the lowest level of education have the kids they intended, compared to 72% of women with a high level of education. The larger fertility shortfall among highly educated women was largely explained by the fact that “highly educated women were considerably less likely to ever enter into a coresidential union, and did so on average three years later than women with a low level of education.” (My two cents: I personally suspect that, given other shifts in the link between women’s socioeconomic status and fertility, the relationship between fertility gaps and women’s education will flatten out and perhaps even reverse in coming decades).

I got kind of confused because it seems like the abstract and body of the study somewhat contradict each other, so: grain of salt. But if I understand correctly, a big portion of the fertility gap is explained by cohabitations ending in separation. According to the authors’ estimates, if all the people who broke up after cohabiting stayed together, and everyone who cohabited got married, then the fertility gap would shrink drastically.

The Power of Parental Warmth

Prior to reading this study, I had never heard of “primal world beliefs” but evidently, they are meant to capture someone’s general view of the world as, for example, “abundant,” or “safe,” or “good.” The aim of the study was to figure out if various aspects of one’s childhood and adolescence influenced one’s view of the world as a young adult (at 22 years old). That is, whether you believe the world to be:

Abundant (“The world is an abundant place with tons and tons to offer.”)

Progressing (“Though the world has problems, on the whole things are definitely improving.”)

Safe (“I tend to see the world as pretty safe.”)

Enticing (“No matter where we are, incredible beauty is always around us.”)

Good (“Most things in the world are good.”)

Analyzing data from eight different countries, including the U.S., the authors didn’t find much evidence that material circumstances in childhood shape one’s “primal beliefs” about the world as an adult. Living in a dangerous neighborhood in childhood or adolescence had little bearing on whether someone viewed the world as safe during adulthood. There was no apparent link between childhood socioeconomic status and the view of the world as abundant. When it came to parenting approaches, “harsh parenting and psychological control” didn’t seem to influence any of one’s beliefs about the world as a young adult. The lone exception was parental warmth, “which significantly predicted young adults' beliefs that the world is Good, Safe, and Enticing.” The authors view these findings as hopeful: after all, parents can’t just will themselves to be richer or for their neighborhood to be safer. But “simply fostering a warm environment in the home—something most parents can attain—holds promise as an avenue for understanding how experiences in childhood and adolescence are related to beliefs in adulthood.”

More Evidence the Economics of Fertility is Changing (for Women)

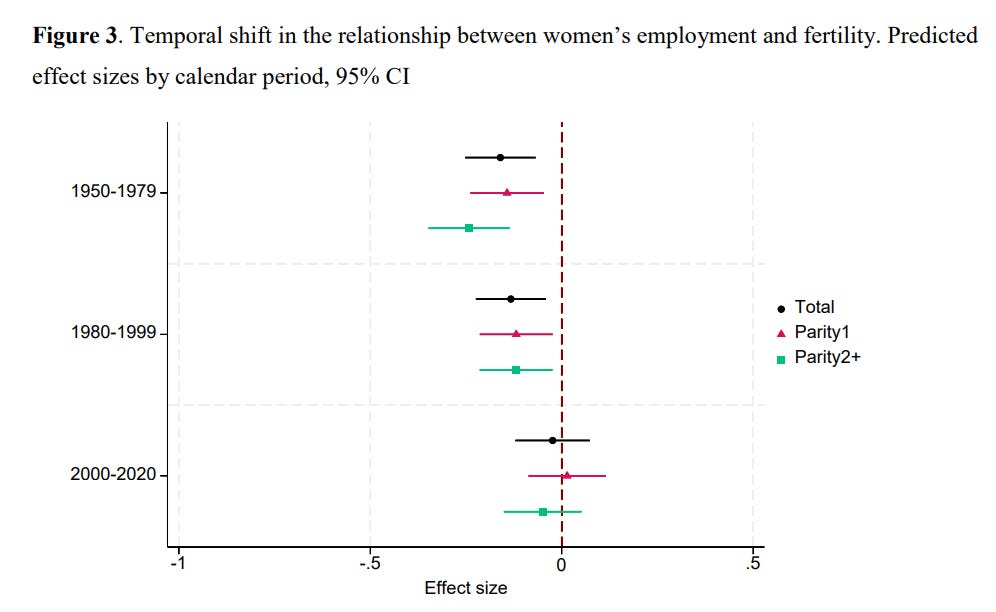

Okay, so, long time Family Stuff readers are already well aware that the economics of fertility seem to be changing (for women, but not really for men. If anything, longstanding links between employment and earnings and male fertility are getting stronger). We have some new data on this front. In 2008, two researchers synthesized the findings from a bunch of studies in Europe and the US and found that “employed women were generally less likely to have children.” Well, the same two authors have now revisited the women’s employment-fertility link in an updated meta-analysis. There are three main findings:

There is a lot of regional variation in the link between female employment and fertility. If you’re looking at the entire time period (which I *think* is covering 1950 to 2020), the negative association between employment and women’s fertility is strongest in the Anglosphere—that is, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States—where “working women are 27% less likely to have children there than those who do not work.” The relationship is weaker but present in Southern Europe (e.g., Italy, Spain) and Germany, almost nil in the Nordic region and Western Europe (France, Belgium, and the Netherlands), and actually positive in Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Russia).

The relationship between women’s employment and fertility has shifted over time: women’s employment was “strongly negatively associated with fertility behavior” during the second half of the 20th century. Between 1950 and 1979, employed women were 15% less likely to have a child than unemployed women. During the 21st century, however, the negative association between women’s employment and fertility largely dissipated. What’s more, “this shift is evident not only among childless women deciding whether to enter motherhood but also among mothers progressing to a second or a third child.”

There is considerable regional variation in the size of these shifts. In the Nordic region and Western Europe, the association between women’s employment and fertility went from near zero to positive, such that employed women are more likely to have kids than non-employed ones. In the Anglosphere, it weakened, but not all the way to zero. Strangely, there’s been no change on this front in the German and Southern European group of countries.

Gaining Affluence Often Means Losing “the Village”

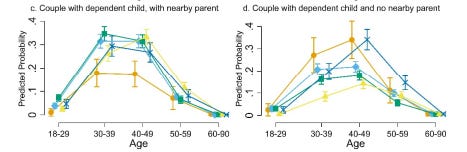

A few years ago, I did a piece for The Atlantic about how affluence “pulls people away from their families.” That is, educational and economic opportunities prompt people to move from their hometowns, resulting in a trade-off between money and kin support. That has obvious implications for parenthood. This study looked at how partnership status, parenthood, and geographic proximity to one’s parents varies with socioeconomic status in Europe, broadly confirming what I found in my piece. As you can see in the chart below, higher SES folks (mustardy yellow line) are less likely to be a partnered parent with a nearby grandparent, and more likely to be a partnered parent without a grandparent nearby. So, yeah, gaining affluence often means losing “the village,” if by “the village” we mean “grandparents.” (You can of course Build-Your-Own village, as I have managed to do over here in the United Kingdom, an ocean away from any grandparents.)

They also found that the whole proximity-to-grandparents thing varies regionally: among European countries, Anglo-Saxon countries (represented by the mustardy yellow line with circles in the chart below) have the lowest levels of coupled parents with a grandparent nearby and the highest levels of coupled parents without a grandparent nearby, at least at younger ages. I wish we knew how the United States fit into this but, it’s interesting that “grandparentless parenting” is such a pronounced phenomenon in the European Anglosphere. [Edit: now that I’m thinking about it, I wonder if this helps to explain why the negative association between women’s employment and fertility is so much stronger in the Anglosphere than elsewhere, as the previous study found.]

“Everything is Terrible But I’m Fine,” But for Teens and Social Media

A couple of years ago, Derek Thompson at the Atlantic wrote a piece titled “Everything Is Terrible, but I’m Fine,” which noted an emerging gap between people’s view of the state of the national economy and their own personal financial well-being. So, for example, while 78% of people in the U.S. said they were personally doing okay financially in 2021, only 24% said the national economy was doing well. There appears to be a similar gap emerging among teens, but on the subject of the harms of social media. According to a new Pew survey, “roughly half of teens (48%) say these sites have a mostly negative effect on people their age, up from 32% in 2022.” Meanwhile, just 14% think social media negatively affects them personally. To be fair, this is up a bit from 9% in 2022. Still, “teens are more than twice as likely to say social media have a positive impact on themselves than on their peers (28% vs. 11%).”

The Mental Health Theory of Low Fertility

Mental health problems are rising and fertility is falling: could these trends be related? This study investigates, using data on Finnish folks born between 1977 and 1980. They found that for both women and men, basically any mental health disorder was linked to a higher likelihood of childlessness, but that the association was particularly strong for those with “severe disorders.” So, to put it in perspective, they estimate that a common mental health disorder emerging at age 25 increases a woman’s odds of being childless by age 40 by 5.3 percentage points, and a severe one by 7.9 percentage points. “Among men, the increase in risk of childlessness is 11.0 %-points for severe and 6.9 %-points for common mental health disorders.” Partnership explains a good deal of the association between mental health and childlessness, particularly among those with more severe disorders. The thinking is that mental health issues, and particularly severe ones, make it harder for people to find and maintain partnerships, which in turn increases their likelihood of remaining childless.

Seems Interesting*

The Impact of Universal Preschool on Child Outcomes (in Japan)

I feel like I never actually read studies about how universal preschool impacts child development (not really my area of interest), but always include them in the round-up (because it’s nice to stay on top of the general findings). Anyway, this study examined the impact of Japan’s expansion of universal preschool on child outcomes, finding that it “significantly reduced juvenile violent arrests and the rate of teenage pregnancy, but did not increase high school enrollment or college enrollment rates.”

The Link Between Delayed Adulthood and Assisted Reproduction

This study, based in Spain, examined the link between the age of “transition to adulthood” (which includes things like completing education, moving out of your parents’ home, entering the labor market, cohabiting with a partner for the first time and becoming a parent) and one’s likelihood of using assisted reproductive technology (ART). They find that women who are late to finding stable employment are less likely to use assisted reproduction. This is particularly true for those without a college degree, which “likely reflects the lower financial resources and reduced professional security faced by less-educated groups.” By contrast, women who are late to moving out of their parent’s house or moving in with a partner are more likely to end up using ART. Among those who actually use ART, the likelihood of it ending successfully in a live birth declines with age, but less so for highly educated women. “Overall, the findings suggest that ART offers limited capacity to mitigate the effects of delayed transitions to adulthood and fertility, especially for less educated women,” the authors conclude.

Partnership, Kids, and Loneliness in Old Age

I ran out of time to read this one in detail, but it explored how loneliness among older folks in 26 European countries varied during the pandemic among people with different family ties (as measured by whether or not someone had a partner, kids, both, or neither) as well as the stringency of a given location’s COVID rules. Broadly, they found that partnership helped to protect against loneliness, and that more stringent COVID rules were associated with greater loneliness (though, I should add, there were some interesting nuances when it came to the interaction between covid stringency and family ties). But I think their most interesting finding is that having children didn’t seem to make much of a difference in loneliness outcomes for those without partners. Unpartnered older folks with and without kids had about the same risk of loneliness during the pandemic. I thought that might have something to do with the fact that COVID rules would disrupt one’s ability to maintain contact with an adult child (who might not live with you) more than a partner (who presumably does), but unless I’m missing something, it seems like the similarity in outcomes between unpartnered parents and unpartnered folks without kids held regardless of COVID rule stringency.

*Didn’t really read these

I've always been extremely dubious about fertility gaps based desired number of children.

If we asked people how many times a week they wanted to exercise, and found the actual number was much lower, we would probably assume the desired number is a mostly made up aspirational signalling thing and that their revealed preferences are a better guide to what they actually want.

I saw one study that followed lottery winners to see if that sudden infusion of a lot of money resulted in people finally having the children they had previously claimed they couldn't afford. Nope, almost no effect. Just like we don't generally see billionaires running running around with even 3 or 4 children. (Other than Elon Musk.)

One problem with all the studies is they aren't longitudinal and fall prey to the end-of-history illusion. I saw one study that followed a group of women in Africa over a number of years, asking them how many children they desired. The number changed with each survey (trending down) but even more notable is they never realised they had changed their mind. They claimed that was the number they had ALWAYS desired, even though the researchers had previous survey data showing it wasn't true.

Another great round-up. On the primal world beliefs paper, an interesting subtlety is that it's only *child reports of* parental warmth that significantly predict Good, Safe and Enticing. Parental reports of parental warmth don't significantly correlate with anything. (The two measures correlate at r = 0.54.)

This adds to a growing body of evidence that parental reports of subjective characteristics are too biased to be reliable (due to social desirability bias, etc.) and some eminent psychologists have recently called for a moratorium on their use. [ https://uclpress.co.uk/book/matters-of-significance/ ]