The Economics of Male Fertility, and Other Interesting New Research

The Inability to Turn Down Sex Makes Mothers Lonely; The Young People Applying for MAID; The Trials of Skip-Generational Living; The Privilege, then Burden of Male Solo Living + more.

Hello Everyone,

Okay so, first of all: yes, this newsletter is a day late. I would have given you a heads up about that except that I myself did not realize it was going to be late until 12:20 a.m. yesterday when my jet-lagged daughters were still up and running around. Second of all, a lot of studies were published this week! The original version of this email included like 15, but I managed to cut it down to a more manageable eight. Let’s get into it!

The Economics of Male Fertility

People often claim that declining birth rates have little to do with economic factors and everything to do with cultural factors. Readers of this newsletter will come to learn that I am quite skeptical of this view, partially because I think the whole culture vs. economy thing is a false dichotomy, and partially because I simply don’t think the evidence supports that claim. Arguably one the strongest counterpoints to the “it’s cultural” viewpoint is that while the relationship between women’s socioeconomic status and fertility is complex and shifting, the relationship between economics and men’s fertility is very well established. Higher earning, better educated men have always been more likely to become dads, and that relationship is only getting stronger over time. A 2019 study based in the Nordic region, for example, found that among men with the least education, childlessness rose from 24% for the early 1940s cohort to 36% for the late 1960s cohort. By comparison, it rose from 11% to 22% among the most educated.

This new Finland-based study went beyond education level to see how fertility varies among men in different fields of education. In general, recent drops in male fertility were steeper in fields with initially lower levels (information and communication tech, arts and humanities, and general education) and milder in fields like health, teaching, and agriculture. (Credit where credit is due: “Men in religion and theology stand out with the highest fertility (2.42), contrasting sharply with fields like philosophy and ethics and language acquisition (around 1.20)”). What’s more, male fertility fell hardest “in fields characterised by higher unemployment, lower income, and lower match between education and occupation.” Ultimately, these “economic uncertainty” metrics explained a huge chunk of Finland’s post-2010s decline in first births (which makes up most of the decline in fertility overall). Income at younger ages was an especially strong predictor of a man’s likelihood of becoming a dad. And the relationship between fertility and both unemployment and income got stronger as the 2010s progressed. “According to our findings,” the authors conclude, “in a Nordic country such as Finland, a secure economic foundation is increasingly crucial for men’s childbearing outcomes.” So….yeah..economic factors matter for fertility.

The Inability to Turn Down Sex Makes Mothers Lonely

Okay, a couple things up front on this one. It’s a study based in Moldova. The sample size is decent (396 mothers and 113 childfree women) but not huge. The authors hypothesized that mothers would be lonelier than childfree women, and that certain gendered risk factors (such as a perceived lack of gender equality in relationships and intimate partner violence) would be associated with loneliness for moms but not childfree women while other gender neutral “established” risk factors (like life satisfaction, partner relationship satisfaction, household task satisfaction, education, and financial stability) would affect both mothers’ and nonmothers’ loneliness equally.

Interestingly, they didn’t find that moms are any lonelier than women without kids. And there were a bunch of differences between moms and childfree women in what sort of established risk factors affected their loneliness. (Things like life satisfaction, partner relationship satisfaction, household task satisfaction, education, and financial stability were risk factors for moms, but not for women without kids. Internet access and work-life balance were risk factors for childfree women, but not mothers). But they did find one gender-specific risk factor that was relevant for moms and not childfree women: sexual autonomy. Mothers without the perceived ability to turn down sexual intercourse with a partner had significantly higher social loneliness scores than mothers who did. It makes perfect intuitive sense to me, but I guess I think there’s something sort of paradoxically profound about that finding: that the inability to reject a bid for sexual intimacy with a partner would make mothers in particular feel alone. It really makes all the Twitter manosphere discussions about “duty sex” seem all the more depressing (if you don’t know what I’m talking about, good!).

The Expanded Child Tax Credit Did not Increase Parental Substance Abuse

There is a large and growing literature about the impacts of the temporarily expanded child tax credit. I follow it all closely because I am a major supporter of giving parents unconditional cash and that was the closest America has come to doing so. One concern people have about giving parents cash is that they’ll just spend it on drugs or booze. This study found that the CTC payments were actually associated with reduced tobacco use among parents. And there were no observed changes in parental use of alcohol, cannabis, or other illicit substances.

Is Caregiving Bad for Mental Health?

I think of caregiving, whether for the elderly or disabled or for children or anyone else, as work. Some people don’t like thinking of it that way, perhaps because they think work carries a negative connotation. But in my view, discussing care as work makes it easier to separate the task itself from the conditions under which it is done. All jobs become bad if you have to do them all the time or under really awful conditions. I’ve worked a number of jobs in my lifetime, and there isn’t a single one that wouldn’t have made me miserable if I’d had to do it 168 hours a week, without any reliable breaks or in total isolation or what-have-you. So, I was not at all surprised by the results of this Belgian study on informal caregiving and mental health which found that “high-intensity caregivers (over 20 h/week) experienced significantly higher psychological distress compared to non-caregivers, whereas lower-intensity caregivers did not.” This is a point that

makes really well in her book When You Care: a lot of the perceived difficulty of caregiving has way more to do with the conditions under which it is done than care itself (which can be rewarding in many ways!).The Young People Applying for Medical Assistance in Dying

I suppose it might seem a little strange to include research on assisted suicide in a newsletter about “family stuff,” but in my view “family stuff” encapsulates anything related to how people in a society get along together. From that view, I think the question of how we ought to respond when someone says they desperately want to end their life is highly relevant. This study took a look at how many young people (under 24 years old) with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands have applied for Medical Assistance in Dying between 2012 and 2021. They found that the number is small (there were 397 applications over the entire time period) but rising (growing from 10 applications in 2012 to 39 in the first half of 2021). Almost half of the applications were retracted by the applicant themselves, and another 44.8% were rejected. Only 3% (12 young people) actually ended their lives with the assistance of MAID, which is less than the 19 (4.3%) who died by suicide or having voluntarily stopped eating and drinking during the application process. For comparison, 1,396 young Dutch people between the ages of 15 and 25 died of suicide over the time period. I found myself both saddened and encouraged by these data: I have deep reservations about the state assisting anyone, let alone a young person suffering from a mental health crisis, in their quest to die. But I am relieved to find that, at least in the Netherlands, it isn’t happening terribly often.

Relatedly, this newly published review of the social determinants of suicide found that while all sorts of adverse experiences impact your likelihood of dying by suicide (justice system involvement, exposure to others’ and parental suicide, firearm accessibility, divorce, experience in foster care, release from incarceration, and midlife unemployment), religious affiliation and being married were protective factors against it.

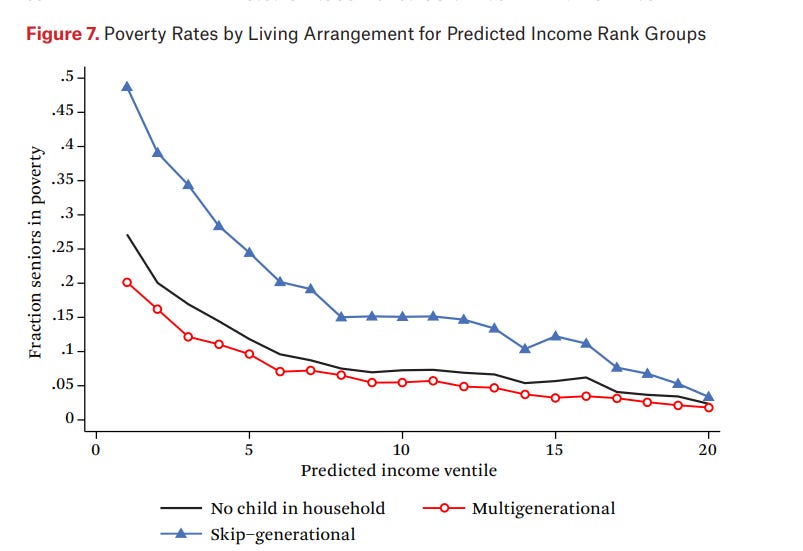

The Trials of Skip-Generational Living

This study looked at living arrangements among seniors with an eye for figuring out who is living with kids under 18 and how it relates to economic disadvantage. They draw a distinction between “multi-generational living,” in which an elderly person lives with their adult child and grandkids, and “skip-generational living,” in which an elderly person lives with only their grandchild. In general, disadvantaged seniors are more likely to live in any sort of arrangement involving kids. But whereas multi-generational living is linked to lower poverty rates than among seniors without children, skip-generational living is linked to higher poverty rates. In other words, multi-generational living is a means of staying out of poverty, but skip-generational living puts the elderly at a heightened risk of poverty.

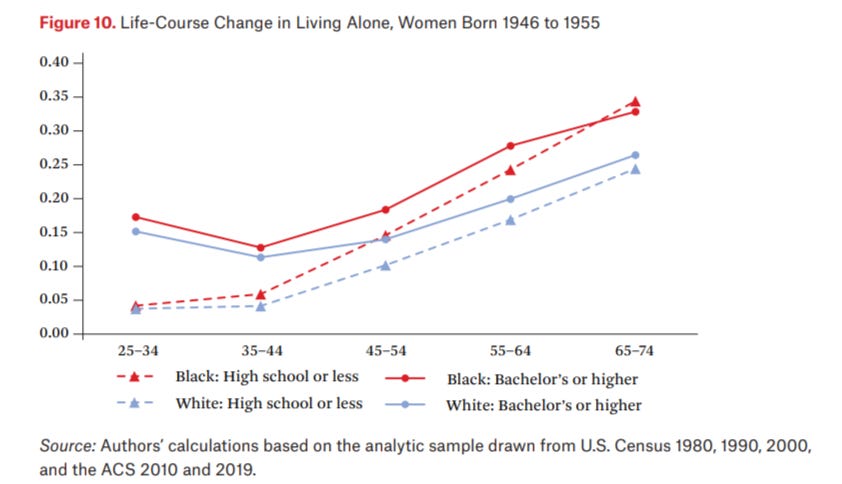

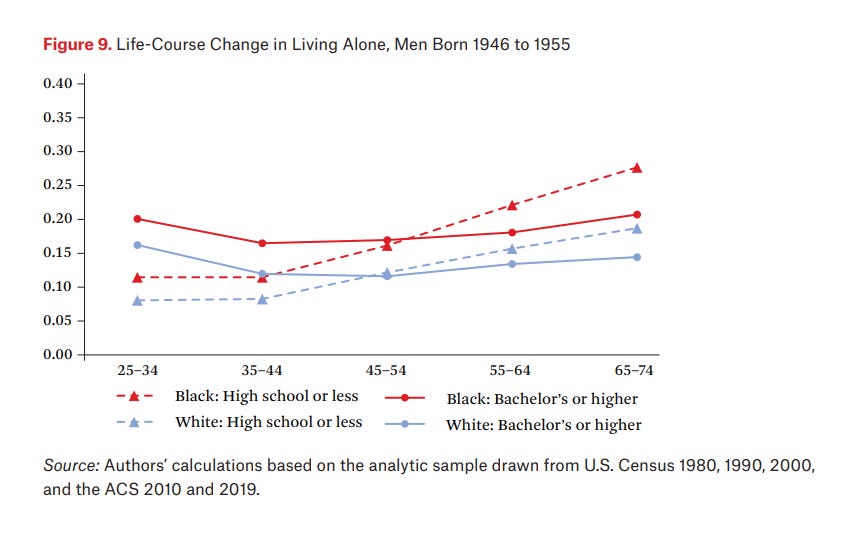

The Privilege, then Burden of Living Alone for Men

There’s been quite a bit of concern lately about the rise of solo living. This study analyzed trends in solo-living between 1980 and 2019 and found there’s been pretty much no change in most groups with the exception of older men, who are increasingly likely to live alone (though still at lower levels than older women). They also found a really interesting pattern in solo living among men over the life course. When men are young, those with the most education are mostly likely to live alone, but as they age, the relationship reverses, and those with the least education are most likely to live alone. In other words, “the nature of solo living seems to depend on the life stage,” the authors note. At younger ages, it’s a privilege. At older ages a burden. Crucially, this life course educational reversal doesn’t exist for women: highly educated women are more likely to live alone than those with less education throughout the life course, though the gap narrows with age.

The Gender Gap in Student Debt

Last but not least, this is a pretty extensive deep dive into the emergent gender divide in educational attainment (women go farther and do better in school than men, across a growing variety of metrics). But it also highlights an underappreciated aspect of this trend: the emerging gender gap in student debt holding. The authors note that “in 2004, women were more likely to carry debt than men only at private non-profit institutions (59 percent to 52 percent).” But “by 2020, women were more likely than men to carry student debt in public and private for-profit sectors as well.” Women and men who take on debt tend to take on roughly similar amounts, but women are now more likely to do so. This is interesting to me. I know everyone is worried about what the education gap portends for men but the fact remains that, despite their higher education levels, women still make less money than men. Unless I’m missing something (and let me know if you think I am!), if women’s disproportionate strides in credentialing aren’t matched with progress in the labor market, then women are more likely to graduate with debt and less likely to be able to pay it off.

It could help to look at what fields women are getting degrees in and taking on debt to do so. My guess is those fields aren't very lucrative but need high credentials, and are also not professional degrees. On this topic, there's this great book called Paying For The Party, that follows women in college. They found that if girls from middle class or lower families ended up in sororities and such, they'd change major to whatever the wealthy girls were doing. But those fields (e.g. sports broadcasting) are just easier and more conducive to partying, and you can't make a living in them unless daddy's connections help you find a low-paying job in NYC but you're wealthy enough not to need the money for ten years. If you're not from that background, those majors make no sense financially, because you end up working in minimum wage jobs at the end of it with massive debt.

There are also much fewer pink-collar professional fields. Nursing is one, where anyone from any background can go into it and graduate with a decent job. There are many that are male dominated, especially engineering.

Anecdotal: I knew these two kids studying at UC Berkeley. Both were from lower-middle class backgrounds, took on debt to do so. He was studying physics, she was studying filmmaking. She spent all her time being involved in campus causes and campus life, and dragged him along. But since she was trying to save money, she would spend her summers working in a restaurant she had been waitressing at since she was fifteen. She didn't do anything relevant to her field because they didn't pay. He wasted time too, but he'd also find internships at physics labs or coding at startups. He was being much less dedicated than she was, but he was being more impactful career wise. Since they graduated, he's spiraled for a bunch of reasons, but his credentials allow him to get a job that pays well for whatever duration he can hold it, and just working for 3-6 months has him good for the rest of the year. She's still working at the restaurant and trying to do online courses on filmmaking. He has paid off his debt despite his whole life being iffy, but she hasn't.

Oof, what a grim study finding about loneliness. My speculative interpretation: the kinds of husbands who make their wives feel unable to say no to intercourse, are generally more possessive, jealous and controlling. Such traits probably extend to other aspects of life like socializing with friends.