The Paradoxical “Fairness” of Childbirth, and Other Interesting New Research

Maybe Joint Custody Isn’t So Great for Moms After All; An Unlikely Case for Helicopter Parenting; What Male Loneliness Crisis?; The Fraught Relationship Between Flexible Work & Gender Equality + more.

Happy Tuesday, everyone!

I said this on “Notes” last week, but I think some of you are starting to get that there is an absolutely massive amount of family-related research published every week, all the time, constantly. I only cover a small part of it. And very little of what I cover is ever covered in the news. I think it’s kinda cool! But I know it can also be overwhelming. With that in mind, I very much encourage you not to take the findings of any one study too seriously, especially as it applies to your own life. Some of you left some very thoughtful comments on last week’s post about the limitations of these studies when it comes to informing individual parenting decisions. I’d just like to reiterate that I 100% agree with that. This is not a parenting advice newsletter—it’s a “what’s going on with human relationships these days” newsletter. Take what you like and leave the rest! (Also, I’ve gotten a small-but-meaningful bump in paid subscriptions over the past two weeks, after a long-running plateau. Thank you to everyone who upgraded! It really means a lot.)

Another Theory of Low Fertility Bites the Dust

If you follow demographic research closely enough, you start to notice that many theories of low fertility are, well, limited. The empirical evidence to support them doesn’t hold up over time, or they make sense in some contexts but not others. This study about childlessness in China is an apt illustration of what I’m talking about.

The Second Demographic Transition theory holds, among other things, that family life is becoming more varied: instead of everyone mostly following a single life-course trajectory characterized by marriage and then childrearing, people are increasingly changing things up and charting their own relational courses. A core prediction of this theory is the decoupling of marriage and childbearing: that people will start having kids without getting married, and married people will forgo child rearing. This particular study analyzed the various partnership trajectories leading to childlessness in China, where marriage and childrearing are still tightly linked. If the Second Demographic Transition theory is correct, you’d expect that, over time, the people remaining childless would steadily become more diverse, including not just those who never married but people who married but never had kids.

Overall, they found that a slight majority of people who remained childless after 40 were never-partnered. Surprisingly (to me, anyway), the next biggest group of childless people was the “early marriage” group, accounting for a quarter of childless individuals and swamping the late marriage group (9.4%), on-time marriage group (9.3%), and unpartnered via divorce or widowhood group (4.9%). In fact, early marriage was the most common pathway to childlessness for women: whereas most childless men in China were never married (52.3%), most childless women married early (51.5%).

On one hand, these findings seem to suggest that childlessness can’t be fully explained by lack of partnership—a solid share of childless individuals, in particular women, not only married but married early! At the same time, they did not find any evidence that the trajectories to childlessness are getting more diverse over time. Quite the contrary, they found that “younger cohorts were less likely to become childless through stable marriages, regardless of their age at first marriage.” And the pathways to childlessness are getting less diverse. In other words, despite what the Second Demographic Transition theory would predict, the link between marriage and childrearing in China is actually getting stronger.

The Fraught Relationship Between Flexible Work and Gender Equality

I am a big fan of workplace flexibility, whether that’s working from home or the ability to choose your hours. But do flexible working arrangements promote gender equality? The evidence on that question is, at the very least, mixed. This Germany-based study investigated how various dimensions of flexible working—remote work, flextime (control over when one works) and working-time autonomy (control over when AND how many hours one works)—affected the division of housework and childcare among German couples. The authors hypothesized that individuals who have these flexibility measures would take on a greater proportion of both housework and childcare than those without them, and that the association would be stronger for women/mothers than men/fathers.

There are some nuances to the findings but, in general, they didn’t find much evidence that any of the flexibility measures were linked to taking on a greater share of housework. Any associations that did show up disappeared after accounting for gender. “It seems as if no flexibility measure was associated with a higher share of housework but that women, irrespective of whether or not they used any workplace flexibility, contributed to a larger share of housework than their male partners.” The findings for childcare weren’t much different, with the exception that flextime seemed to affect the share of childcare mothers and fathers did in opposite ways: “when mothers used flextime, their share in childcare was even larger than when they did not use this flexibility, while for fathers, this pattern was the opposite.” This fits with some other research suggesting that men and women are drawn to flexible work arrangements for different motives, and use them in different ways. Women use flexibility to tend to their kids and households, while men use it to increase their productivity at work.

One thing to keep in mind here is that this study was looking at how flexible working arrangements are associated with the share of housework and childcare that someone does, rather than the amount. And they couldn’t account for partners’ use of flexibility arrangements. I say that because I can’t quite figure out if this study conflicts with the one I shared last week—that one, which was based in the US, found that on WFH days, dads did considerably more solo and joint childcare than days working out of the home.

What Male Loneliness Crisis?

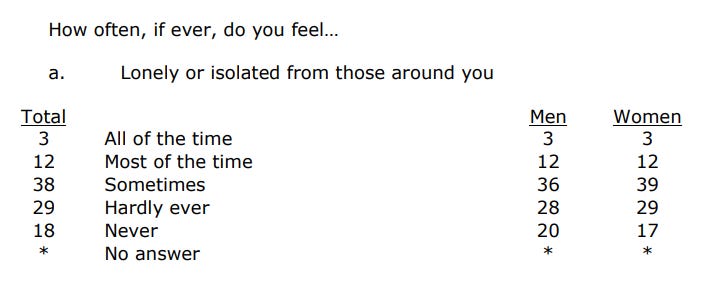

A big, new Pew survey about social connections, loneliness, and gender went up last week. It will likely get covered in lots of ways by lots of people, so I won’t go super in depth here, but a couple of interesting points jumped out. One is that, for all the talk of the male loneliness crisis, men did not report being lonelier than women or having fewer friends. This held across all age groups. That said, men do seem to lead more isolated lives in the sense that they are less likely to reach out to a spouse, their mother, friends, or other family member if they were in need of emotional support.

Breaking loneliness out by a variety of sociodemographic indicators, there was a pretty clear inverse relationship between loneliness and socioeconomic status—the more education you have, and the more income you have, the less likely you are to be lonely. Cohabiting and unpartnered folks were far more likely to be lonely than those who are married. One finding that sorta took me by surprise is that young people are way more likely to report feeling lonely than the elderly. Only 6% of those over the age of 65 say they feel lonely or isolated from those around them all or most of the time, compared to 24% for those in the 18-29 category. Something something social media?

An Unlikely Case for Helicopter Parenting

I was unaware of this strand of research but, apparently, there is quite a bit of evidence suggesting that student obesity rises in the summer months and falls while school is in session. This study investigated the possibility that a year-round school calendar, which spreads school out over the year, might mitigate this phenomenon. Turns out it doesn’t: Obesity prevalence did not shift between the school calendars. I suppose that’s interesting, but to be honest I'm more curious about the phenomenon in general. There’s something sort of bleak about the fact that time spent in school—where kids sit at desks for huge chunks of the day—is actually an improvement, from a physical activity and nutritional standpoint, over the alternative.

Apparently, the working theory is that school is just a more structured environment. “Schools limit screen time, limit opportunities to snack, and cause families to enforce regular sleep schedules,” the authors wrote. Plus, schools schedule physical activity and provide meals that, if not super healthy, are more nutritious than what a lot of kids get elsewhere. Meanwhile, “when school lets out, constraints loosen, and children are freer to behave in ways that increase obesity and reduce fitness.” Big if true, as they say—that the freedom that attends summer break leads kids move less and eat more crappily. Seems like a defense of helicopter parenting: perhaps a century ago, a kid left to his own devices would spend his summer vacation running around with friends. Today, he will just stay inside and eat junk food and play video games.

Maybe Joint Custody Isn’t So Great for Moms After All

As mentioned in a previous newsletter, joint custody arrangements are on the rise in both the U.S. and Europe. There is reason to believe this is a positive development, not only for kids but for their moms. Sharing responsibility for the child could at least theoretically make it easier for a single mom to balance work and caregiving, buffering them against poverty while offering them more leisure time for socializing and perhaps even dating. And joint custody might reduce conflict between co-parents, because no one “lost” the custody battle. Then again, all the coordination, communication, and perhaps conflict involved in moving kids from house to house and joint decision-making could be a bit of a headache. Plus, if the mom doesn’t trust the dad to care for the child adequately, sharing custody with him could simply cause anguish and worry.

The findings of this particular study give us reason to doubt the value of joint custody (for moms, anyway). They assess life satisfaction among mothers in different custody arrangements in Belgium, Finland, and Germany, and found pretty substantial differences between the countries. In Belgium, where joint physical custody (JPC) has been standard for considerably longer than elsewhere, they didn’t find any difference in life satisfaction between moms in joint or sole custody arrangements. In Finland and Germany, joint custody was associated with higher life satisfaction, but the differences disappeared after they introduced various controls. Both of these findings suggest that differences in maternal life satisfaction across custody arrangements are driven by selection effects—i.e. the fact that the moms opting into joint custody tend to be more highly educated, financially well-off, and have more cooperative co-parents. The fact that joint custody had essentially no impact on Belgium, where it’s been normalized, and had the largest impact in Germany, where joint custody remains a rarity, suggests that once everyone hops on the joint custody train, the perceived benefits start to disappear.

The Paradoxical “Fairness” of Childbirth

Okay so we all know there is a gender housework gap. But how do couples actually feel about it—that is, do they perceive their gendered division of labor as unfair? This study examined how men and women perceive the fairness of their divisions of labor in the time leading up to and following the birth of the first child. Throughout the whole timeline, men perceive themselves as doing less than their fair share, and women perceive themselves as doing more than their fair share. But whereas men’s perception was pretty stable over time, women's perception shifted considerably throughout the stages of childbearing.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, the time just before and just after childbirth is the sweet spot of perceived fairness among new moms. In general, compared to childless women, mothers-to-be are more likely to report doing more than their fair share. But in and around childbirth (that is, from conception to the newborn stage), the relationship switches, and mothers are actually more likely than childless women to report a fair division of labor. The share of women reporting that they do less than their fair share is highest just before childbirth. And right after childbirth is when women are most likely to report that all is fair between them and their spouse. Unfortunately, the honeymoon ends at about 6 months postpartum and things seem steadily unfairer to mothers as time goes on, not only returning to, but surpassing pre-pregnancy levels of unfairness.

One mysterious aspect of all this is that while there was a relationship between one’s share of housework and perceived unfairness (i.e. “the higher one’s share in housework, the more they feel the division of labor is unfair to them”), the childbirth-fairness-sweet-spot doesn’t appear to be explained by changes in the actual division of labor between moms and dads. I am kind of stumped on this one! I would love to hear anyone’s theories for this childbirth-induced bout of domestic bliss.

My guess re the fairness question is that very close to the birth and shortly after, mom is extremely vulnerable and needs help to do most things. I felt as if I was a burden on the family during this period, and reassurance that I wasn’t, made me feel cared for. As mom gets her energy back though, this effect goes away.

I wonder if a lot of the drop in feeling like things are unfair towards the end of the pregnancy comes from the fact that she becomes more incapacitated around the perinatal period and so her husband and village steps up more during that period. But after she recovers a little and gets back on her feet and sleep is better, so to speak, she is once again expected to take over the lion’s share of domestic work all by herself. Toddlers get more physically and emotionally demanding, but at least they are not as physiologically demanding as a fetus or a very fresh baby (when you’re waking up once every 2-4 hours). So women are expected to shoulder it all. According to everyone (including ourselves most of the time), if we are not literally incapacitated, it’s our job.