Why Finnish Moms Stay At Home, and Other Interesting New Research

The Evolution of Coming Out; The Formula Shortage Boosted Breastfeeding; Most Teens Say Gender is Determined by Sex at Birth; America Already Has Subsidized Childcare (Social Security) + more.

Happy Tu-... er.. Wednesday everyone,

First, I’m sorry this newsletter is coming a day late. Crazy week and all. Second, thank you to everyone who read, commented on, or shared my piece about admitting that we need parents. I’m delighted that it resonated with so many of you and I really appreciated hearing people’s perspectives on what did and did not motivate them to have kids. Finally, this round-up is a little more policy-centric than usual. Just a heads up, in case that’s not your thing.

The Evolution of Coming Out

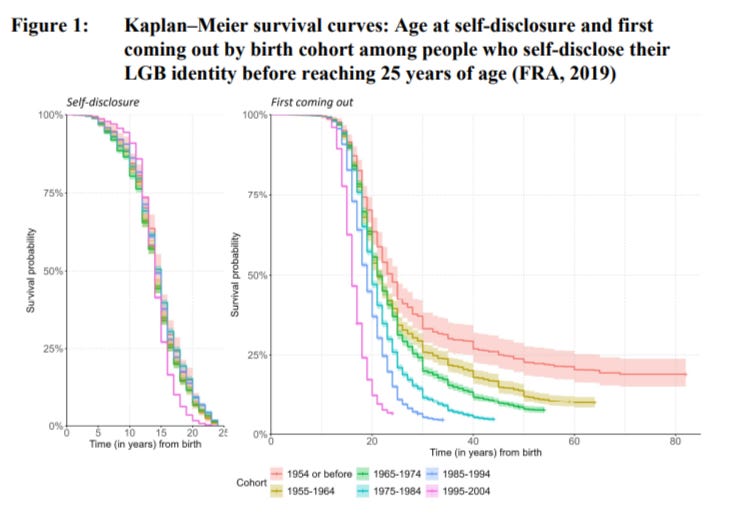

An increasing number of young people identify as LGBTQIA. This study of LGB folks in Europe tried to figure out if and how the age of two key milestones—self-disclosure (realizing you are gay or bisexual) and disclosure to others (“coming out”)—has shifted over time, and varies by gender, sexual orientation, and country.

The patterns by gender and orientation were kind of interesting. Gay men self-disclose the earliest, at about 14, but they have the longest gap between self-disclosure and coming out. Women in general tend to have shorter gaps, particularly bisexual women. Basically all lesbians eventually come out (97.74%), and coming out rates are pretty high (over 90%) for everyone but bisexual men, only about 77% of whom actually come out.

Contrary to what the authors expected, the mean age at self-disclosure hasn’t budged much over time. But the age of coming out has dropped pretty significantly over time. So it’s taking less time for people to go from realizing they are gay or bisexual to letting other people know.

One sort of surprising finding is that the countries with the lowest age of self-disclosure and narrowest age gaps were in Eastern European countries, while some of the highest ages of self disclosure were in the fairly open-minded Netherlands and Denmark. One possible explanation is that the normalization of homosexuality in those countries puts “less pressure on individuals to question their sexual identity, thus leading to higher age at self-disclosure, on average.” Meanwhile, higher “homonegativity” found in Eastern and Southern Europe could actually prompt people to interrogate their sexuality earlier.

Why Finnish Moms Choose Home Care

Technically this study was first published in June, but it’s part of the February 2025 issue of the Journal of Family Issues, and thus reappeared in my inbox: so, off on a technicality. For context, Finland has (what I consider) a very cool, pluralistic family policy framework that facilitates both formal and informal childcare arrangements. Once a child hits 9 months old, as paid maternity/parental leave (the paid portion of which you are eligible for even if you don’t have a job) wraps up, parents have the option of choosing between a spot in childcare or using a home care allowance, which can be used either to enable a parent to stay at home, or to hire other non-parental care. Almost 90% of mothers of children born in 2018 opted for the home care allowance for at least a little bit. Half of them did so for a year or less, and half of them longer.

This study tried to figure out why women opted for the home care allowance, focusing on a subsample of “stay-at-home” mothers who live with a spouse and have permanent work contracts—that is, mothers who could probably work if they wanted to. (Just a note: I can’t tell if this sample includes women who are specifically not working, or if it also includes those who are actually working but just opted for the home care allowance in order to hire a nanny or pay a trusted relative to look after their kids.) The most common reason mothers listed for using the home care allowance was that the child was too young for daycare, with about 9 in 10 listing that as “quite” or “very” important. The next most common reason was that they just liked staying home. Next was the simple conviction that “a mother of a young child must stay home.”

The authors did a bit of analysis to figure out how responses varied according to socioeconomic status (SES). The normative notion that mothers ought to be at home with their kids was more prevalent among those with lower SES, as were concerns about the quality of daycare. But interestingly, the idea that the child was too young for daycare is the one reason that did NOT vary by SES. Basically all moms, rich or poor, agreed that a “one-year-old child was too young to start in daycare outside the home.” Apparently, parents there tend to think 18–24 months is a suitable age for a kid to start daycare. I would love to know how this “suitable age of daycare start” varies across countries! (My guess is that among the many Polish moms at my kids’ school, the answer would be like 7 lmao.)

Teen Moms Smoke a Lot

This study, based in Canada, broke down trends in prenatal substance use between 2012 and 2022. Of the nearly 1 million pregnant women included, 12.3% consumed at least 1 substance during pregnancy: 2.4% used cannabis, 2.4% consumed alcohol and 9.2% smoked tobacco. To be fair, there was a steep decline in tobacco use over the decade, falling from 11.3% in 2012 to 6.1% in 2022. But even by 2022, fully a quarter of teen moms (12 to 19 years old) and another 16.2% of moms in their early 20s smoked!

Cannabis use rose, by contrast, from 1.2% in 2012 to 4.3% in 2022. Again, it’s much higher among teen moms (over 20%). Unfortunately the data don’t give us any insight into how often or when pregnant women were using these substances. I’m not sure this is justified, but I think I feel less judgey about drinking a glass of beer or wine during pregnancy than cigarettes or cannabis, so I was kinda surprised that the latter two are actually more common. And then yeah, damn, the teen rates. Kinda nuts.

Food Stamps Are Good for Pregnant Moms

Speaking of pregnant moms, we’ve got a more uplifting story to tell here. This study looked into whether a. food insecurity in pregnancy is associated with perinatal complications and b. the receipt of food assistance can mitigate the effect. The answer is yes, and yes. Food insecurity during pregnancy was fairly common in this sample (14%) and was linked to a heightened risk of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, preterm birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission, BUT, the associations pretty much disappeared among those who received food assistance in the form of CalFresh or SNAP, California Food Access Program (CFAP), WIC, or something else. The authors note that there are some self-selection concerns that make it hard to draw conclusions about the impact of food assistance—by that I think they mean that the sort of people who actually sign up for assistance may be different than the sort of people who don’t. But the heightened risk of complications held even after accounting for both neighborhood and individual socioeconomic characteristics, so, that’s something.

The Formula Shortage Boosted Breastfeeding

This is sort of a controversial one, but this study that was published at the very end of December (JAMA just published a summary, which is why I just saw it), found that America’s 2022 formula shortage boosted average breastfeeding initiation rates by about 2 percentage points. The increase was steepest among mothers with lower education levels, black mothers, those on various forms of state assistance, and those in less populous areas—that is, mothers who are more reliant on formula. Meanwhile, the shortage had no significant impact on breastfeeding among “college-educated individuals, those covered by private insurance, or those in counties of more than 100 000 people.”

I’m really not sure what to make of this. The authors note that this shift highlights some potential for closing socioeconomic disparities in breastfeeding rates and while it’s sort of icky to think about the shortage of formula in a positive manner, I do agree it suggests it’s possible to move the needle. But the “how” here matters, I think. Maybe in the context of the shortage, hospitals or even workplaces made a greater effort to support breastfeeding among these more vulnerable mothers. Or maybe this just indicates that (surprise, surprise) the formula shortage fell hardest on the most vulnerable women. I’m not interested in leveraging desperation to boost breastfeeding rates.

Most Teens Say Gender is Determined by Sex at Birth

Pew just published a survey intended to gauge how common it is for people to know trans or nonbinary people. The headline takeaway was while adults are more likely to know someone who is trans, teens are more likely to know someone who is nonbinary. But then it also surveyed people’s views on how gender is determined. Most people, and indeed most teens (69%), say that whether a person is a man or a woman is determined by sex assigned at birth. There’s a big difference by political party—democrat teens are way more likely to say gender can be different than one’s sex at birth. But still, 50% of them disagree. And teens are pretty much split when it comes to comfort with they/them pronouns.

America Already Has Subsidized Childcare (Social Security)

Through Social Security, America supplements the income of the elderly to spare them from poverty in retirement—what, if anything, does that do for children? This study explores that question in a very direct way, noting that the share of kids living with a Social Security-eligible adult is rising. (Interestingly, they note that as of 2019, only 4% of minors live in households receiving TANF income (TANF is the program that people typically think of as “welfare”), a considerably smaller share than those in households receiving Social Security!) Estimating how Social Security eligibility impacts resources in such households, they find that it doesn’t actually increase net income because people receiving Social Security work less. (They did find that it reduced deep poverty.) BUT they note that it does “increase the number of adults available for home production, which could yield more time investment in children.”

I was happy to see that they acknowledged that prospect, first of all. But I think its implications go well beyond multi-generational households. To the extent that Social Security income allows grandparents to care for grandkids, it is possible to think of Social Security as a form of subsidized childcare. This is one reason that raising the age at which people become eligible for Social Security is not as straightforward a fix for the pressure of low fertility as it might seem. Keeping the elderly at work means they are less likely to be around to help care for grandkids, which has implications both for labor supply and fertility!

I'm so intrigued by the daycare/going back to work situation for Finnish moms (and anyone else who thinks group care isn't appropriate and/or desirable at young ages) - my question would be how many children are these women ending up having? Because staying home for a good long while before going back to work doesn't really make sense if you're.... having multiple kids? Like by the time you're doing that you might be having another child and starting over? So I can see this working with very low fertility families. This is part of the reason many women just.... care for their kids themselves, because they plan on having more than a couple. Maybe I'm missing something!? haha It just seems to suit a very particular mother, and I suppose that's fine! Maybe Finnish families are quite small.

Great stuff! Re: what to make of the formula shortage study, perhaps it reinforces the notion that poor women who use formula disproportionately do it for reasons other than medical necessity (ie they're physically capable of breastfeeding but use formula for reasons e.g. their job isn't breastfeeding friendly). Not the most solid evidence, but maybe it lightly suggests we should give these women the support they need to breastfeed if they want to.