Why Finnish Dads Don’t Stay at Home, and Other Interesting New Research

The Complexity of American Fatherhood; The Upside of Full-Day Kindergarten; The Countries Where Young People Are Getting Happier; The Link Between Parental Regret & Longing for Grandparenthood + more

A note for newcomers: Welcome! This is a weekly round-up of newly published research on demography, family policy, and other family stuff. Some of the studies included here may be pre-prints or working papers and have not yet been peer reviewed. And while I have done my best to summarize their findings accurately, in the words of Ebenezer Scrooge, “I am a mortal, and liable to fall.” In other words, I hope you brought a pinch of salt with you.

Hello everyone,

Happy Independence Day to all who celebrate! I probably won’t be celebrating much, what with living in the United Kingdom and all. We don’t get the day off here, obviously. Just business and ballet lessons as usual. In fact, I spent my morning attending my 6-year-old’s school assembly, where she played Queen Victoria in a play about the English monarchy.

A quick housekeeping note: in response to feedback from a few (potential) readers, Family Stuff is now an AI-art-free publication. I didn’t realize so many people found my little ChatGPT illustrations off-putting. It was fun while it lasted, but I aim to please and have no problem ditching the AI stuff if it’s bothering people. Also, don’t forget that until August 18th (when the paywall goes up on these AI-free round-ups) you can get an annual subscription to Family Stuff for 50% off!

The Complexity of American Fatherhood

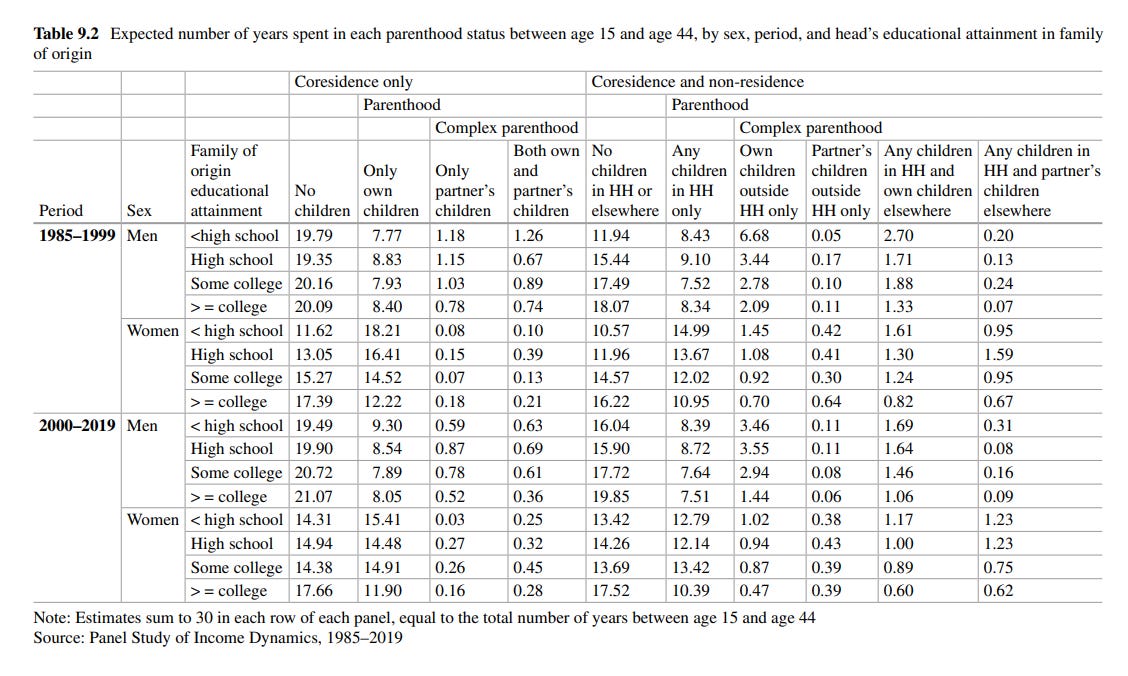

We tend to think of parents as people who live in the same household as their biological offspring, but, of course, that isn’t always the case. Plenty of American parents don’t live with their biological kids, or they are stepparents to kids living in their own household or elsewhere. This study explores how these experiences, which the authors refer to as “complex parenthood,” differ by gender.

Broadly speaking, the authors find that complex parenthood is a predominantly male phenomenon. For example: “mothers spent more than 95 percent of their parenting years living with their own biological or adopted children only, compared to 80 percent of coresidential years for fathers.” When you rope children living elsewhere into the analysis, moms spend 20-23% of their parenting years in a complex parental role, compared to 35-40% for dads. Fathers’ heightened parenthood complexity is mainly due to the fact that fathers spend more time living apart from at least one of their biological or adopted children. So for example, between 2000 and 2019, men spent an average of 2.67 of their parenting years with their bio or adopted children living elsewhere compared to 0.79 years for women.

The authors also found that complex parenthood tends to involve different things for men and women as well. For fathers, complex parenthood is more likely to involve living away from their own biological or adopted kids and living with stepchildren. For mothers, it is more likely to involve being a stepparent to children living somewhere else. That makes sense, given that moms tend to get custody after a split.

There were, perhaps unsurprisingly, pretty big class differences when it came to how much time people spent in a complex parental role. But interestingly, the class differences were considerably larger for men than for women. For example, between 2000 and 2019, women without a high school diploma spent an average of about 1 year with their biological kids living elsewhere, compared to just under half a year for women with a college degree or more. But men who didn’t graduate from high school spent about 3.5 years with their biological kids living elsewhere, compared to less than 1.5 years for men with a college degree or more. In other words, socioeconomic status shapes men’s experience of parenthood far more than it shapes women’s.

Why Finnish Dads Don’t Stay at Home

I like to think of Finland’s home care allowance—a cash stipend that parents can opt to take in lieu of a spot in a formal daycare—as the “problematic fave” of family policies. We’ve already covered how popular it is, with about 90% of Finnish parents opting to use it for at least a little bit. We’ve also covered research suggesting it’s linked to worse outcomes for kids. But yet another reason that Finland’s home care allowance is considered problematic (to some) is that although it is technically a gender neutral benefit, it is overwhelmingly used by moms. In 2020, for example, 92% of home care allowance recipients in Finland were mothers. The heavily gendered use of home care allowances has led some to argue that they function “as a trap for women as it reduces their labor force participation and attachment to the labor market to a much larger extent than men's,” as the authors of this new study put it. This is one reason that Sweden scrapped its similar “cash-for-care” policy in 2016.

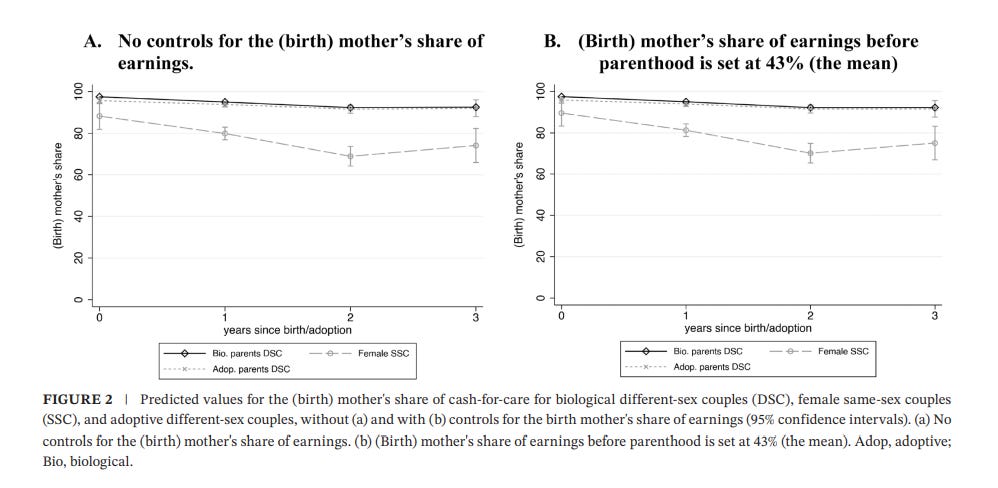

This study explored why the use of Finland’s home care allowance is so gendered by comparing its use among female same-sex couples, adoptive parents in different-sex couples, and biological parents in different-sex couples. If the gendered use of the allowance has something to do with the biological experience of giving birth to the child, then presumably its use among adoptive couples would be more evenly split, and within female same-sex couples, the birthing mother would be more likely to use the allowance. Likewise, if the gendered use of the home care allowance has something to do with the relative earnings of the parents, then “couples in similar financial situations should make similar decisions on how to allocate cash-for-care, regardless of partner sex or the presence of a birth parent.” Long story short, they didn’t find much evidence for either the biological or financial explanations.

Starting with the biology theory, the authors did find that among female same-sex couples, the birth mother was more likely to use the home care allowance, which is consistent with the idea that the act of giving birth might drive the gendered use of Finland’s home care allowance. But that theory was upended by the fact that adoptive heterosexual parents, neither of whom give birth, split use of the care allowance very similarly to different-sex biological parents. As you can see in the chart below, in both adoptive and biological heterosexual couples, the mothers’ share of the care allowance hovers around 90%. When it came to finances, in all couples, the moms (or birth mothers, in female same-sex couples) were significantly more likely to use the care allowance, “irrespective of whether they were the primary or secondary earner.” So it’s not like people are just having the lower earning spouse take the care allowance. As such, the authors conclude that, having ruled out finances and biology, “gender norms appear to have the strongest role in shaping cash-for-care use.”

What Happened When America Started Offering Full-Day Kindergarten

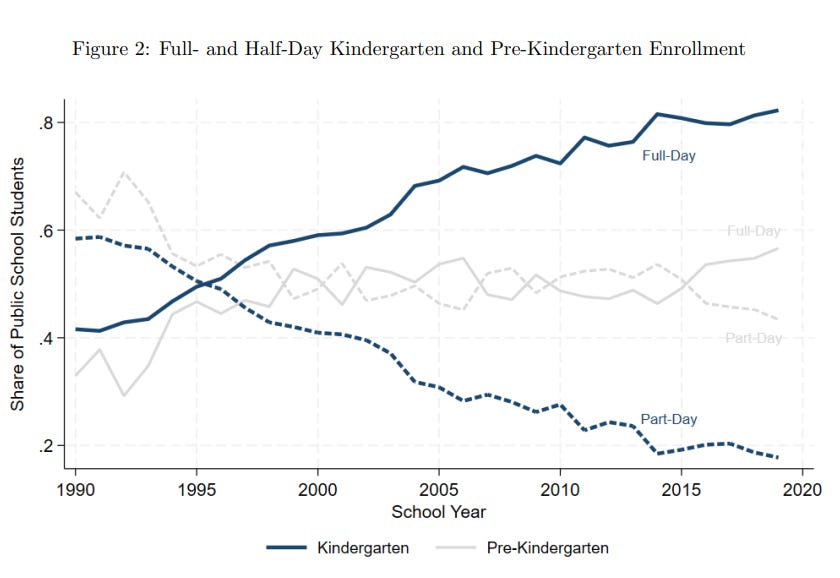

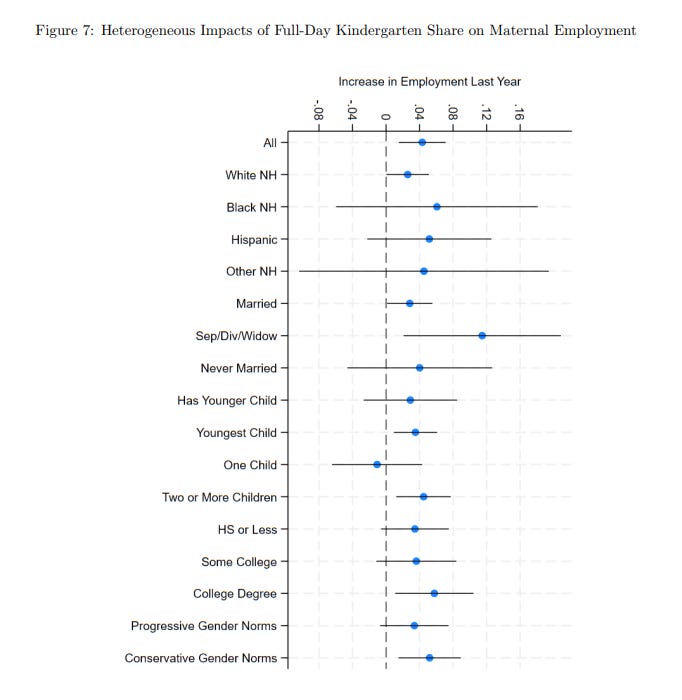

Over the past few decades, a ton of U.S. states went from offering half-day kindergarten programs to offering full-day programs. As a result, between 1992 and 2022, the share of public-school kindergarteners attending on a full-time basis nearly doubled from 43% to 83%. The authors of this study assess whether the shift to full-day programming played a role in increasing labor force participation of mothers with kindergarten-aged kids. And it did! “A 10 percentage-point increase in full-day kindergarten enrollment increases maternal employment in the last year by 0.43 percentage points,” the authors write. That’s bigger than it sounds: It means that expansions in full-day kindergarten programming explain about a quarter of the increase in employment among moms with 5- and 6-year-old children between 1992 and 2022. As such, “these gains are even larger than the aggregate gains associated with the initial introduction of kindergarten.” Given that even full-time school doesn’t cover the full work day, the authors suggest that perhaps extending “school-day coverage to better align with a typical work schedule and commuting could produce even larger effects.”

The Countries Where Young People Are Getting Happier

Until pretty recently, it was a truth universally acknowledged that life satisfaction and happiness are U-shaped with respect to age—that is, people’s happiness is high in their youth, drops in mid-life, and then starts to rise again as they age. Meanwhile, “negative affect” or ill-being, has tended to be hump-shaped with respect to age—it is low in youth, peaks in mid-life, and then declines with age. But emergent evidence suggests that, as youth mental health has deteriorated over the past several years, the age gradients of well-being and ill-being have started to shift. For example, a study published earlier this year that looked at shifts in well-being among young people in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States found that instead of being U-shaped, well-being now rises with age in those countries.

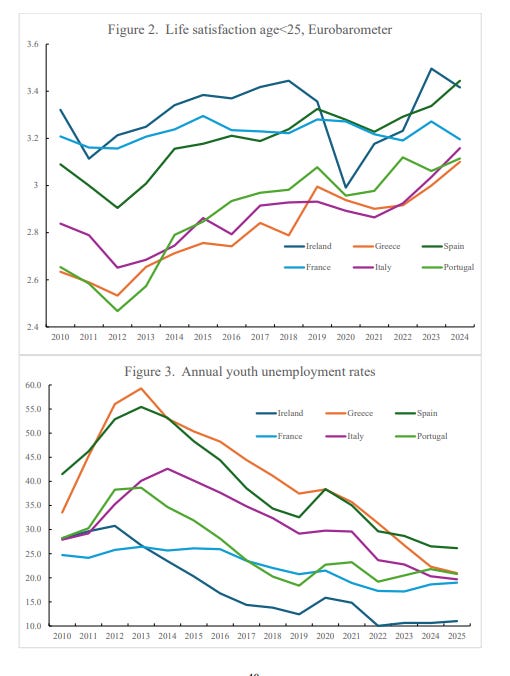

This working paper assesses how the relationship between life satisfaction and age has shifted in 21 Western European countries since 1973. Broadly, they again find that the longstanding well-being U-shape is gone. But when it comes to individual countries, the age/well-being link is shifting in different ways. In a whole bunch of northern European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK) life satisfaction now rises with age. But in a handful of southern European countries (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Spain and Portugal), life satisfaction now actually declines with age. This is due to the fact that in these countries, life satisfaction has bucked the trend and is rising among young people, smartphones be damned. This improvement in life satisfaction among the young in Southern Europe appears to be driven by “the rapid decline in youth unemployment from its 2015 peak.” I think this finding sort of complicates the question of why youth well-being is cratering in so many countries, no? After all, social media exists in Italy, too.

Seems Interesting*

The Link Between Parental Regret and Longing for Grandparenthood

This study on parental regret—by which we mean “domain-specific regret about one’s own parenting history”—found that people with stronger parental regrets also have a stronger desire to become a grandparent. The authors argue “that regrets about how one behaved during one’s children’s childhood can lead one to resort to fantasies about idealized realities with future grandchildren, expressed in a longing for grandparenthood.”

Does Your Child Need Speech Therapy Or Are They Just Young for Their Class

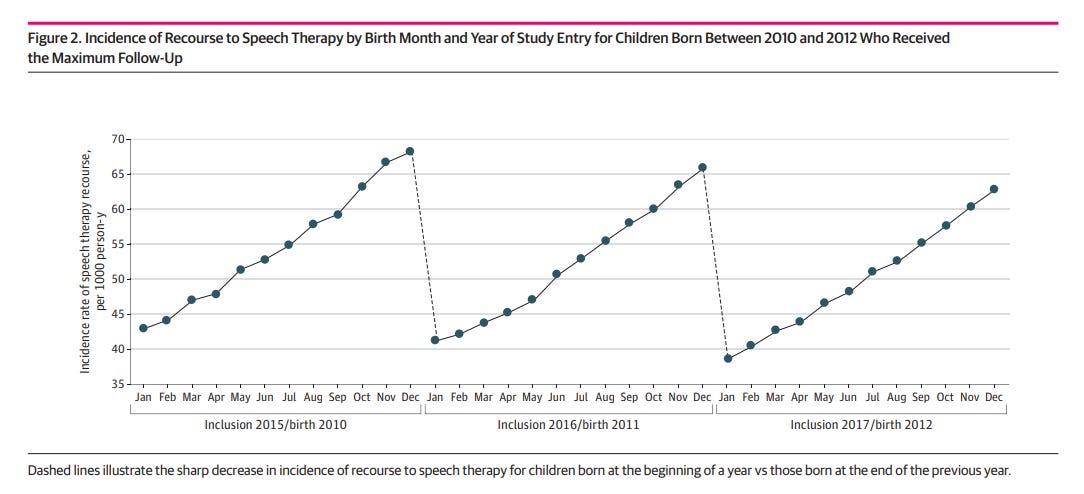

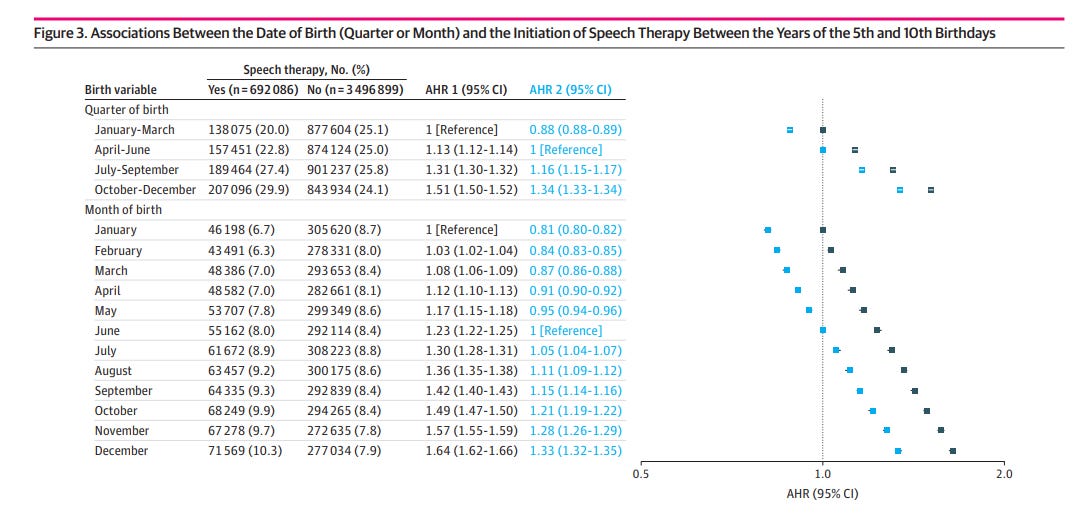

This study took a look at how one’s relative age within their school class influences one’s likelihood of being referred for speech therapy in France. Basically, the younger you are relative to your classmates, the more likely you’ll be clocked as needing speech therapy: “Those born in December (the youngest) were 64% more likely to start speech therapy than those born in January (the oldest).” Looking at their figures, it’s actually sort of remarkable how linear the relationship is being relative age and speech therapy initiation. Per the authors, “these findings suggest that age-related relative immaturity may be misdiagnosed as a learning disability or relative maturity may lead to underdiagnosis of this disorder.”

*Didn’t read these

On the Finland data, It's interesting that biology for the researchers seems to stop at "birthing the child" and gender norms take over thereafter.

As someone whose kids are just getting to school age, it floors me how little the school day actually lines up with the work day. People just accept this year after year??!?!