The Case for Having a Baby in College, and Other Interesting New Research

How Childhood Shapes Fertility; The Housing Theory of Spousal Age Gaps; Why Dads With Breadwinning Wives Won’t Take Paternity Leave; Turns Out Siblings Aren’t Bad for (Firstborn) Kids + more.

Happy Tuesday Everyone!

Hm…do I have anything interesting to mention up here? Not really! So let’s get right into it.

.

How Childhood Shapes Fertility

Can I actually explain this one without messing up? I’m not sure. It’s the sort of paper I’d want to chat with the author about before communicating its findings (that’s true of every paper tbh, though some more than others), but I’m going to give it a shot anyway. Let’s get some of the basics down: native-born and non-native-born residents of a given country often have different fertility rates. There’s a considerable body of research devoted to figuring out if, how, and why immigrants and their descendants adapt to the childbearing norms of their destination country. We already have evidence that the age at which one arrives in a country influences this process. This study tried to figure out how the age at which one migrates impacts childbearing among immigrants who arrived in Sweden as kids.

If I understand correctly, the authors found that, yes, there’s a relationship between age at arrival and childbearing among child immigrants, particularly among those from countries where people tend to have lots of kids. For both men and women from high fertility contexts, arriving in Sweden earlier in childhood puts considerable downward pressure on the number of kids one has (see the bottom panel of the figure below): “Compared with those who arrived as teenagers, immigrants who arrived at preschool ages have more than 0.5 fewer children (as do individuals of the second generation).” The relationship doesn’t seem to be entirely driven by selection (the fact that perhaps people who immigrate are different than those who stay put) or reverse causality (the fact that people with more kids might be less likely to immigrate). As such, the study supports the idea that “an immigrant’s fertility will depend on their exposure to childbearing norms and behaviors during childhood.” This is a phenomenon I find sort of fascinating—the fact that the number of kids a person has is so deeply shaped by their childhood.

The Intergenerational Consequences of Birth Order

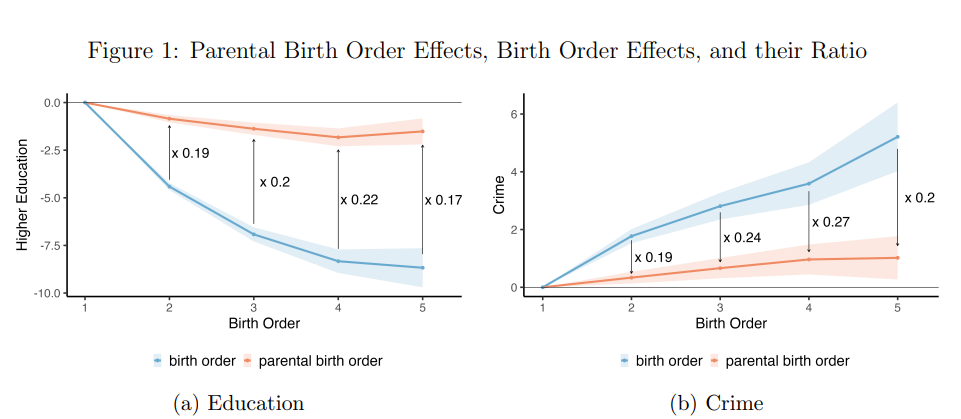

My childhood experience shaped who I am as an adult—but is it shaping my kids as well? Will the quality of parenting that I received as a kid influence how my kids ultimately turn out? This study gets at these questions by investigating the intergenerational impact of birth order, using birth order as a sort of proxy for parental investment. There’s a sizeable body of research on how birth order affects kids’ outcomes, with first-born kids generally faring better than their later born siblings when it comes to education, earnings, and the like.

It turns out that later-born kids pass about 20% of their own income disadvantage onto their kids. So, “the income of third-born parents is 3 percentiles lower than that of first-born parents, whereas their children’s income is 0.6 percentiles lower than that of children from first-born parents.” Higher parental birth order also negatively impacts education, and increases criminality among boys. Paternal birth order is particularly influential when it comes to crime.

As I’ve tried to articulate before, I never know what to make of this sort of research. On one hand, this is evidence that parental investments matter, and that’s cool! On the other, as a middle-kid-of-five, idk…I have a hard time taking this sort of stuff seriously. It’s not that I doubt the findings, but reading a study like this doesn’t make me think “oh I guess I should stop having kids.” It makes me think “I should send this to my little brother so I can rub it in his face that, as the 5th born, his kids will turn out even shittier than mine.”

Turns Out Siblings Aren’t Bad for (Firstborn) Kids

Somewhat related to the study above, this working paper doesn’t exactly push back on the birth order privilege idea, but it does complicate the idea that having siblings negatively impacts kids—that is, first born kids anyway. By studying a population of one-child families that undergo IVF treatment for a second child in Denmark, the authors are able to estimate the impact of having siblings on school performance, personality traits, and school happiness among first-born children. The main finding is that “first-born children with and without siblings (for exogenous reasons) do equally well in terms of school test scores in math and reading, in terms of personalty traits agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability, and in terms of overall school happiness.” In other words, “at least in the Danish context, the presence or absence of siblings does not have any substantial causal effect on the cognitive and non-cognitive development of first-born children.” Again, it doesn’t tell us anything about the impact of having siblings for later born kids, only that first-borns are generally spared the downsides of having siblings. Just another dimension of first-born privilege, perhaps!

Why Dads With Breadwinning Wives Won’t Take Paternity Leave

When a wife out-earns her husband, you might expect the latter to deprioritize his own career and shoulder more domestic labor—but that isn’t always how it works out. One explanation for this, sometimes referred to as “doing gender,” holds that men and women who violate gender norms in some way will look for ways to uphold them in others. So a bread-winning wife may try to “compensate” for her departure from traditional gender roles by taking on more housework and childcare. Or men who make less than their wives may shirk domestic duties as a means of reasserting their masculinity. This study attempted to figure out if there was any truth to this theory when it comes to whether or not Italian dads use paternity leave and parental leave.

In order to understand how the authors investigated this, you need to understand a couple of details about how paternity leave and parental leave work in Italy. Paternity leave is fully compensated and nontransferable—that is, only dads can take it, and the household’s income is unaffected regardless of whether or not he does. Parental leave, by contrast, is partially paid and usable by either parent. The leave-taking parent gets only 30% of their pay, which means that the financially savvy move is to have the lower earning parent take the leave. This is one explanation for why this parental leave is overwhelmingly taken by mothers, who are much more likely to be the second earner. But for the minority of couples in which the mother is the breadwinner, the financially sensible decision would be for the dad to take the leave.

Fascinatingly, the authors found that as the mom’s earning share rises, the likelihood of the dad taking paternity leave falls, while the likelihood of him taking parental leave rises. So basically, when the costs of “doing gender” are fairly low, couples do in fact conform to gender roles, perhaps as a means of compensating for the norm-violating female breadwinning. But when they are high, they just stick with what makes economic sense: for dads to take the leave.

Another Disappointing Study about Paternity Leave

On another note, this working paper found that Quebec’s paternity leave program, which gives dads 5 weeks of earmarked leave, had sorta lackluster impacts on labor market outcomes. The reform led dads to take leave at much higher rates, and it reduced their immediate earnings. But beyond that, it had no impact on “earnings, employment, or the probability of being employed in a high-wage industry for either parent.” On top of that, they found “no evidence that the reform changed social norms around care-taking and family responsibilities.” This is not the first study to find as much. That said, researchers are divided on how we ought to interpret these meh findings. Ann-Zofie Duvander, a demography professor at Stockholm University and an expert on fathers’ use of parental leave, once told me that “teasing out the degree to which [earmarked paternity leave] is responsible for improving women’s career advancement and earnings is tricky—its impact likely manifests gradually and works in conjunction with other family policies,” but that if you can’t see it’s having an effect in places like Sweden, then “you’re living in another reality.”

The Case for Having a Baby in College

There is considerable evidence that, from a career standpoint, delaying childbearing has some advantages for women: to name just one example, this recent paper notes that the U.S. motherhood wage penalty is shrinking over time, but that the effect is driven by women who delay child-rearing. Meanwhile, the pay penalty for “women who had their first child before their late 20s is generally similar to that of previous cohorts.” But is having a baby on the early side always bad for women’s career prospects? This study investigates how having a baby in college or grad school impacts labor market outcomes for Danish women.

Their findings are pretty intriguing. On one hand, having a baby while in school harms your educational outcomes. “Student-mothers are significantly more likely to drop out of their formal education and achieve lower grades compared to non-student-mothers,” for example. On the other, even though having a baby in college or grad school tends to delay graduation, it doesn’t seem to hurt the mom’s earning profile. Of those who actually complete their studies, student moms “tend to catch up,” earnings-wise, to those who become mothers after entering the labor market, and some groups actually surpass their non-student-mother peers. By age 40, the annual earnings of those who had a baby in undergrad are actually higher than those of non-student-mothers. (Those who have a baby while in a master’s program don’t fully catch up to their non-student-mom peers by age 40. Womp…this is what I did lol.) Also, student moms tend to have more kids than their non-student-mom peers (2.2 vs. 1.7 by age 40). This might simply reflect differing preferences, but it could also indicate that having kids earlier allowed student moms to more easily achieve their fertility goals.

According to the authors, the results suggest that, “under certain conditions, such as those provided by Denmark's generous welfare system, relatively early motherhood does not necessarily result in a significant long-run earnings penalty for high-skilled women.” So, at least in Denmark, having a kid in college might be a semi-decent strategy for achieving your desired family size without harming your career prospects.

The Housing Theory of Spousal Age Gaps

I was unfortunately unable to access the entirety of this study, but I’m including it anyway because it’s intriguing. Broadly speaking, spousal age gaps tend to decline as countries develop, but apparently, China’s spousal age gap has been rising since the 1990s. The authors investigate the possibility that this countertrend might be linked to surging housing prices there. Apparently, in China, men are expected to purchase a house prior to marriage (!). Rising housing prices means that it takes longer for “men to accumulate the wealth required for home ownership.” As a result, the thinking goes that, men will tend to “postpone marriage more than women, resulting in a wider spousal age gap.” The authors find that, yes, among urban couples in eastern regions of the country, housing prices significantly increased the spousal age gap. “A 10% surge in housing prices is associated with a 0.22 years increase in the spousal age gap and a 2.98 percentage point increase in the likelihood of urban couples having a 3-year age gap and a 1.71 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a 5-year age gap in marital age.” Surging home prices led both urban men and women to delay marriage, “but the effect for men is almost double than for women.”

The case for having a baby in college makes sense when you consider that 'crunch time' for establishing your career mostly happens in your early to late twenties. This is the time when young professionals can prove themselves, make key relationships, get on a 'partner' track (or not), and generally point their careers in a direction for success. Which is not to say there aren't second chance in life, but if you've hit age 30 without some significant career achievements you'll have a very hard time being considered for the highest paying, most demanding career track jobs.

In comparison, how you do in college is relatively unimportant.

As the first of eight siblings, I think about birth order and outcomes a ton. There's a 20 yr gap between myself and my youngest sibling, and it's interesting to see how different the paths of the oldest siblings have been relative to the youngest. Anyway, fascinating stuff!