The American Women Who Aren't Giving Up On Marriage

On the rise of women who are "marrying down."

A little over a week ago, The Wall Street Journal published an article titled American Women Are Giving Up on Marriage, claiming that, due in part to growing gender gaps in educational attainment and economic success, more women are choosing the single life over settling for lower-status men. Last week,

published a follow-up to the WSJ piece, in which she claims that “there's an undeniable link between the rise of women and the demise of marriage.” Yet another article published in Fortune in mid-March presented data compiled by Divorce.com suggesting that marriages in which women are the primary breadwinners are at a greatly heightened risk of divorce.The common thread in all these pieces is the notion that women’s strides in higher education and in the labor market have made it harder for them to find suitable partners. According to Venker, this is because, unlike men, who are happy to marry women who earn less or have less education than they do, women “resist marrying down,” which means that the supply of men who meet their standards is shrinking. In other words, “women would rather go it alone than be the dominant partner in their relationship.”

I don’t think this narrative is entirely without merit (I’ll get to why in a minute), but there is one major problem with it, which is that while marriage rates have certainly declined in recent decades, plenty of women are still getting married. And in many cases, women are going for exactly the sort of men that Venker and others insist they won’t. Like it or not, women are increasingly “marrying down.”

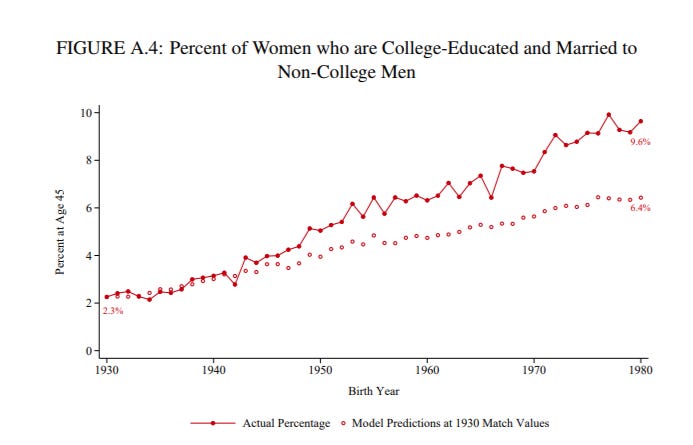

Marriage rates among college-educated women have been broadly stable over the past few decades, even as college-educated men are in increasingly short supply. This is possible because, as a recent study demonstrates, a growing share of college-educated women are marrying men without four-year degrees. As I detail in my latest for The Atlantic (that’s a gift link), which takes a look at what we know about such “educationally hypogamous” marriages, “among Americans born in 1930, 2.3 percent ended up in a marriage where the woman had a four-year degree and the man did not. Among the cohort of those born in 1980, that figure was 9.6 percent.”

A bit more from my piece: “In fact, women are now more likely to marry a less-educated man than men are to marry a less-educated woman. Christine Schwartz, a sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, shared data with me on trends in the educational profile of heterosexual married couples from 1940 to 2020. According to her calculations, in 2020, American husbands and wives shared the same broad level of education in 44.5 percent of heterosexual marriages, down from more than 47 percent in the early 2000s. Of the educationally mixed marriages, the majority—62 percent—were hypogamous, up from 39 percent in 1980. ”

Now, credit where credit is due: women are certainly not indifferent to the earning power of their prospective spouses. As you can see in the chart below, when it comes to the financial fortunes of men without college degrees, there is a stark difference between those who are marrying college-educated women and those who aren’t. The inflation-adjusted earnings of the former have risen over time, while the earnings of the latter have tanked. So college-educated women are dipping into the pool of men without 4-year-degrees and plucking out the highest earners. Other research suggests that although wives with more education than their husbands are more likely than others to be the primary breadwinners in their marriages, they typically aren’t.

That said, I don’t think the evidence suggests that women will only marry men who earn more than them. Just because the non-college-educated men college-educated women are marrying have done comparatively well for themselves financially doesn’t mean they are always the primary breadwinners. A substantial minority of women married to men with less education than themselves do in fact out-earn their husbands. In European countries, the proportion of wives earning more than their husbands ranges from 20% to 40% among educationally hypogamous marriages.

Whether these couples are happy is, of course, another question. But the data there is perhaps a bit more complicated than the Fortune article I mentioned at the top of this piece suggests. For one thing, while it used to be that educationally hypogamous marriages were at a higher risk of divorce than others, that association has disappeared over time, in both America and Europe. And while the Fortune article pointed to a 2013 study to back up Divorce.com’s finding that female-breadwinning marriages are at a heightened risk of divorce, it curiously left out one of Schwartz’s more recent studies suggesting that is no longer the case. So the evidence on the stability of female-breadwinning marriages is, at the very least, mixed.

(For what it’s worth, after I saw the Fortune piece, I reached out to Schwartz asking what she made of it. She noted that the 2013 study it cites has been criticized because “it pools data from a long time horizon and does not examine change over time.” She told me that she’d need to take a look at the data Divorce.com used to see why their results differ from her’s. She acknowledged that their analysis could be correct, but noted that “they seem to be only reporting descriptive statistics—that is, they are not controlling for things that may be associated with BOTH divorce and wives out-earning their husbands.”)

I think it is nigh undeniable that women’s educational and economic advancement have allowed them to be choosier about whom they marry, and that many would rather go it alone that marry someone they don’t actually like or respect. But the impression I got from my reporting on the subject is that women’s marital preferences are less rigid than Venker and others would have you believe. I think there are a whole lot of women who don’t care all that much about educational gaps. They know that educational achievement doesn’t linearly translate to intelligence or competence. Some of the women I interviewed seemed to take pride in the fact that their husbands could hack it in the U.S. labor market without a college degree. And though men’s ability to contribute financially to their households certainly matters to women, I do not think the evidence supports Venker’s claim that women “would rather go it alone than be the primary provider.” Marriages rates would be quite a bit lower than they are if that were the case.

Was there any info on what the lesser-educated men are doing to earn money? For instance, are they in the trades or entrepreneurs? I ask bc I’m seeing a shift in what a degree can do for someone, both in terms of the education it actually offers (e.g., no longer an indication of “best and brightest”) and in terms of the opportunities it affords for future earning potential. (Plumbers in many big cities are earning six figure salaries, for example.)

So I do wonder if Venker’s underlying points still kind of stand- that most women are not keen to marry someone significantly less intelligent or unable to be a self-starter/ good provider- but that degrees no longer indicate whether or not someone is a deadbeat (to put it bluntly!)?

I’ve also noticed a big difference between European and American attitudes towards masculinity, femininity, the ability to work for pay, having degrees, etc- such a big difference that honestly I would expect studies to show very different things.

Great article, Stephanie, and I love this conversation. Particularly since I work with couples every week who are navigating the fact that the wife is the major breadwinner. There is so much to unpack with this dynamic but to be clear: You're right that there are also women who are choosing to ignore their hypergamous nature and marry men who are less educated or less wealthy, in large part bc they have no choice. For many of them, it's either that or remain single. There is a growing cohort of women who are choosing the latter, but there are still plenty cases of the former as well. The real issue, imo, is buried in your piece here, though: how those marriages are faring is another matter altogether. My last post didn't touch upon that, but that is where my heart lies—much more so than in the marriage rate, per se.