Marriage is Booming! (Among Rich Women), and Other Interesting New Research

The rise of religiously mixed couples; a case for "redshirting" the girls; the varieties of single parenthood; America's big, complex families (and the feminization of Western families?)

Hello everyone,

I am publishing this newsletter from Vienna International Airport. I spent Thanksgiving weekend visiting my American sister and her fam in the-middle-of-nowhere Austria. It was a bit random and, with four little kids in a small flat on the grounds of a 14th century Monastery in the cold Alpine winter, a little chaotic—but delightful nonetheless. Fortunately, I still found time (mostly late at night) to go through all the interesting studies that hit my inbox this week, so let’s dig in.

The Rise of Religiously Mixed Couples

Technically, I first saw this study the week before last. I declined to include it in last week’s round-up because I’m trying not to overwhelm readers with too much about fertility (with which I have a bit of a fixation). And the broad takeaways of the study, which explored the possibility that secularization (defined as the decline in church membership) might help to explain falling fertility in modern Finland, aren’t that surprising. Basically, the authors find that a. Churchgoing Finns have more kids than non-Church-going Finns and b. That an ongoing decline in church membership helps to explain the birth rate decline in Finland of late.

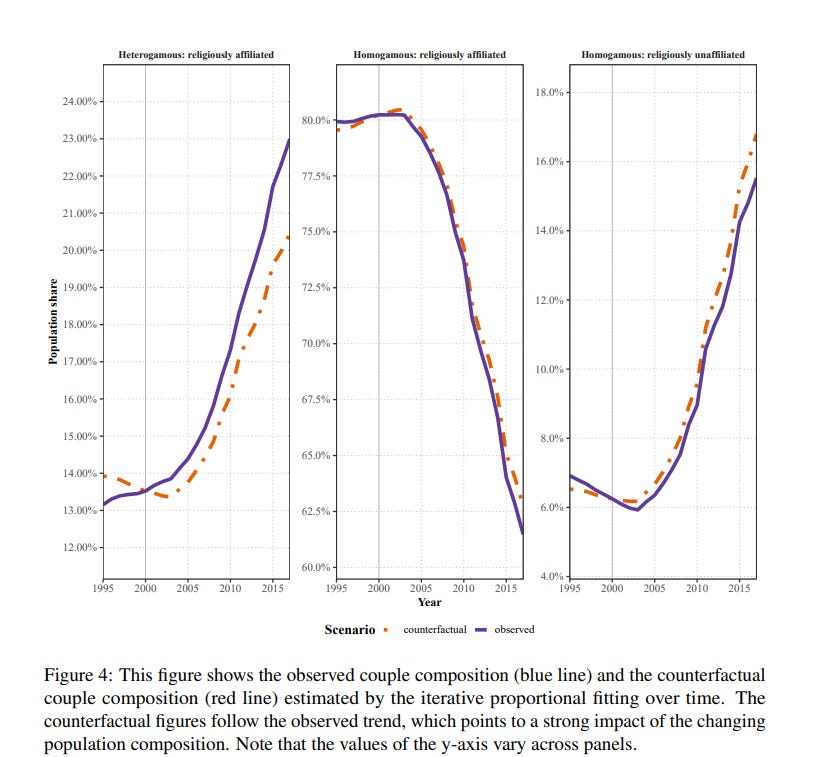

But the authors probed a bit into how secularization is pushing the birth rate down, which is where it gets interesting. They found that the decline in church membership has coincided with a steep increase in religiously-mixed couples—that is, couples in which one partner is religious and the other is not—and a steep decline in the share of couples with two religious partners (“religiously homogenous couples”). This makes some intuitive sense: when fewer people are religious, the pool of potential partners is dominated by those who don’t attend a church. In response, religious people increasingly marry nonbelievers. As it turns out, this trend has implications for fertility, because religiously mixed couples have fewer kids than religiously homogenous ones. (The gender of the religious partner matters, too: couples in which the female partner is religious have more kids than ones in which only the male is religious). In other words, secularization has a self-reinforcing effect on fertility—it lowers the birth rate even among the remaining religious population by changing who they partner up with.

Marriage is Booming (for Rich Women).

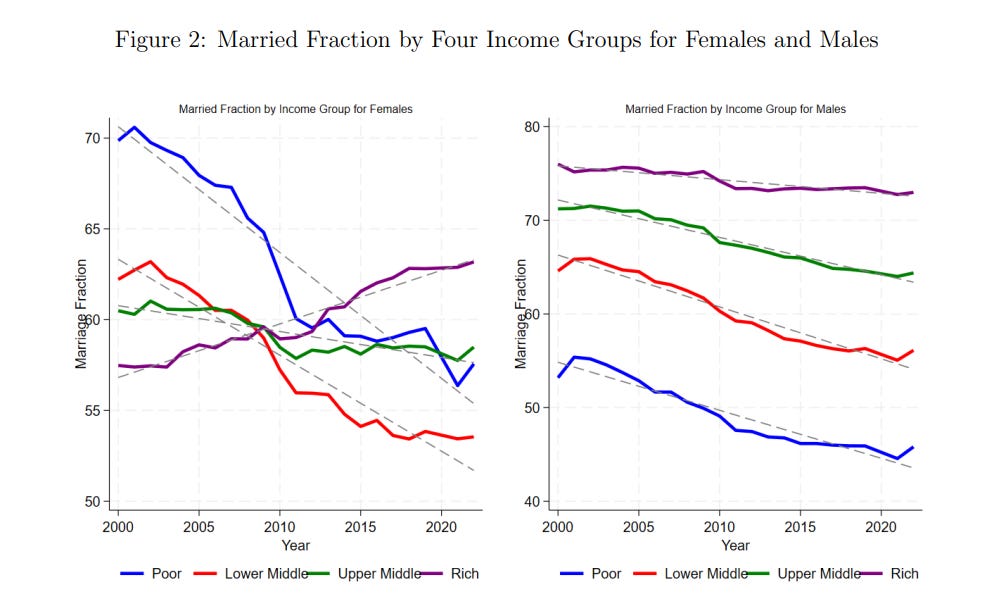

In case you haven’t heard, Americans are falling out of love with marriage—or at least, fewer Americans are getting married. A new paper dug a bit into how marriage rates vary by income and found that there is one major exception to the retreat-from-marriage trend: high income women. This is a slightly tricky phenomenon to explain. There’s some evidence to suggest that changes in the relative wages between the sexes—the fact that the gap between male and female earnings has shrunk—can help to explain why marriage rates have declined. As women have established their own earning power, finding a husband to support them has become less pressing. That is all well and good, but it can’t explain why marriage rates are actually rising among women who earn the most. Interestingly, the author of this paper offers evidence that a decline in working hours among men helps to explain this counter-trend. I suppose that, for a high earning woman (presumably one with her own demanding job), a partner with more time on his hands is a particularly valuable asset.

Redshirt the Girls? Redshirt Everybody?

If you subscribe to The Atlantic, or generally follow the evolving discussions about how boys are faring in modern society, you may be familiar with Richard Reeves’ argument that we ought to “redshirt the boys”—that is, let boys start school a year later than girls to help ensure they are socially and emotionally prepared to succeed academically. Reeves argues this is a reasonable move mainly because a. Boys have been falling behind girls in school for decades and b. Boys’ brains develop a bit more slowly than girls. But this study, which assessed how school starting ages affect personality traits, offers us at least one reason to consider redshirting the girls. Starting school later led to “a persistent reduction in neuroticism, particularly among women.” That’s notable because more neurotic people tend to wind up with worse emotional well-being, less education, and lower wages.

One thing that I’m not totally clear on in the redshirting debate is how much of the benefit of a delayed school start comes from having a better match-up between one’s capacities and grade-level expectations, and how much comes from being relatively more capable than one’s classmates. If it’s mostly the former, then I guess maybe we should just redshirt everybody—maybe school just needs to start later. If the latter, then redshirting boys and girls brings us back to square one, no?

Maybe It’s Not Just a “Piece of Paper.”

Over the past year or so, there’s been a whole lot of chatter about the so-called “two-parent privilege”—that is, the fact that kids in two-parent families fare better on a variety of outcomes than their single parent peers. It is certainly well-established that kids in single parent households are at a heightened risk of poverty. This is true basically everywhere, but is especially true in the U.S. (Matt Bruenig, of

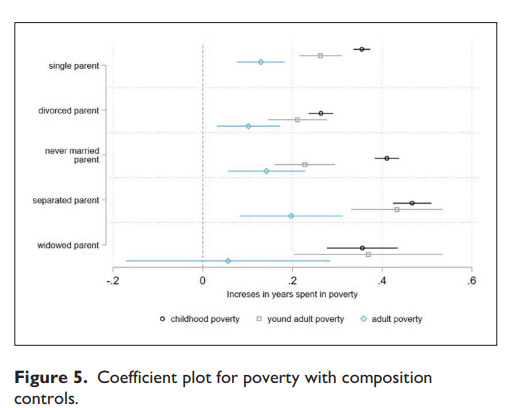

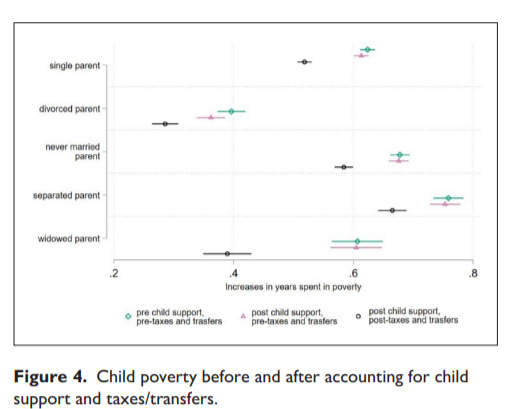

, once pointed out to me that the single-parent child poverty rate in Denmark is actually lower than the two-parent child poverty rate in the U.S. So we could alleviate the outsized hardship of single parents if we wanted.). But while we often talk about single parent households as one homogenous category, there are a lot of different ways to become a single parent. This study investigated the possibility that different pathways to single parenthood (widowhood, divorce, separation, and never marrying in the first place) might have different implications for a kid’s risk of poverty, and they do! Kids of never married and separated single parents face a substantially larger “poverty penalty” than those of divorced or widowed parents. “Children of divorce” fared best, and their poverty penalty mostly disappeared by the time they reached adulthood.

Some of these disparities are due to compositional differences (age, education, employment, occupation type, etc…) and some are due to social policy. The social safety net is far more robust for widows than anyone else. And divorced parents are considerably more likely to get child support than never married or separated parents. But gaps remain even after accounting for these.

I found this paper helpful because I find that sometimes discussions about whether marriage is good or bad lack precision. There’s a narrative floating around that marriage as an institution is bad for women, one that saddles them with a disproportionate amount of unpaid work and leaves them financially vulnerable. There is certainly a sense in which that is true, but I think this study gestures at the truer truth, which is that the financial vulnerability supposedly brought on by marriage is better understood as the financial vulnerability brought on by bearing someone’s child. And that formalizing partnership formation and dissolution through marriage and divorce can help to insure against such vulnerability.

My Big, Complex American Family (+ the Feminization of Western Families)

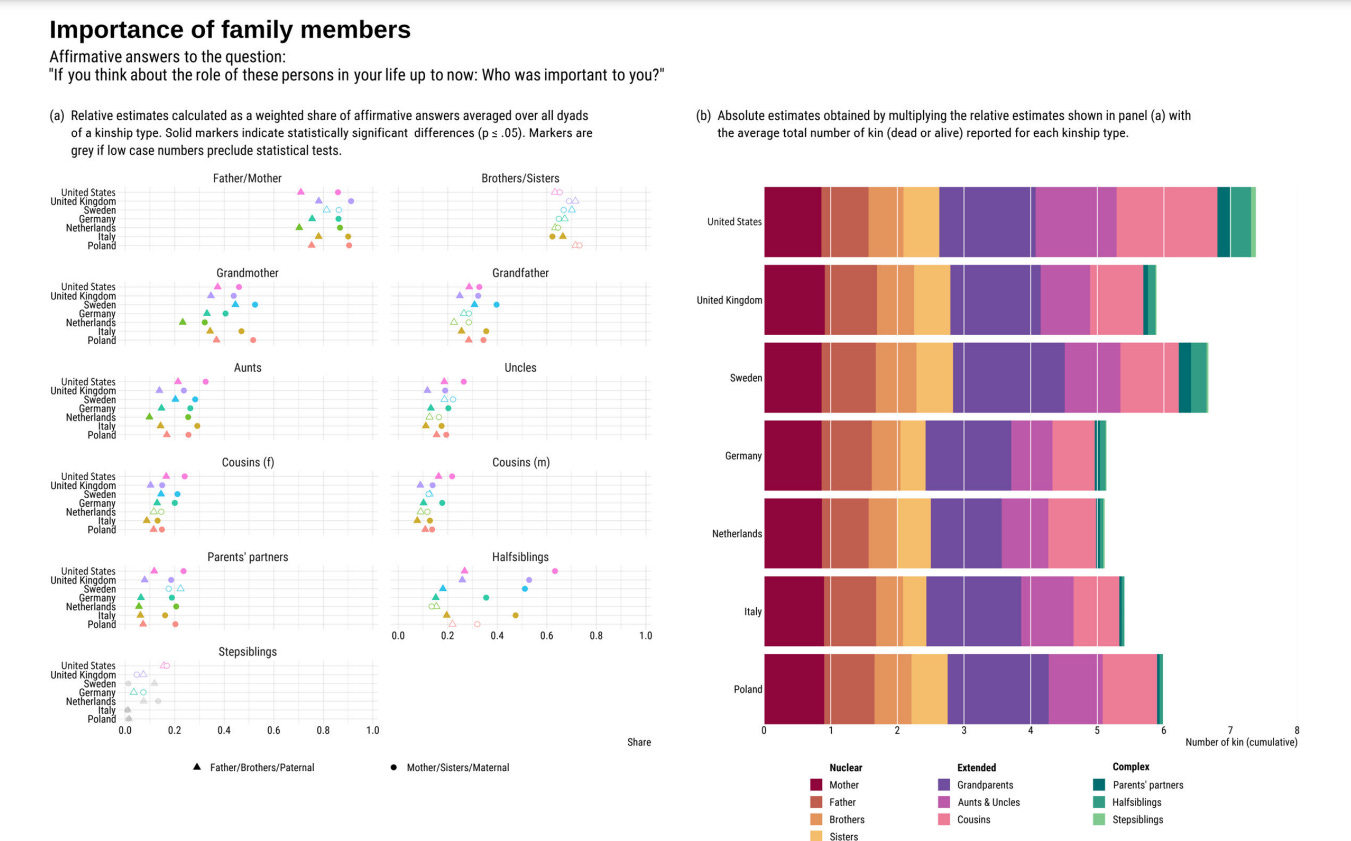

Okay there’s a lot to cover here but I’m going to try to keep it as brief as possible: This very cool study mapped kinship networks in a handful of Western countries (Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States). When considering the sorts of kin that people consider “important” to them, the US stood out in a couple of interesting ways. Americans put a heightened emphasis on extended kin, such as aunts and uncles. And complex kin (step-siblings, half-siblings and step-parents) featured more prominently in American kin networks than elsewhere, not because we value those relationships more, but because we simply have more of them. (The USA is quite exceptional, compared to most European countries when it comes to family complexity. In the United States, “multi-partner fertility,” i.e. having children with more than one partner, accounts for 20% of all births. It’s 9% in Sweden, which had the highest rate of multi-partner fertility of all the European countries included in the analysis). The high number of complex kin partially explains why Americans have the largest overall networks of “important” kin.

On a somewhat separate note, the authors also found pretty strong evidence of what's sometimes called the “matrilineal tilt,” or the tendency for people to have stronger bonds with their mom’s side of the family than their dad’s. In all seven countries, “maternal kin were more often identified as important, more frequently contacted, emotionally closer, and overrepresented among those who could be counted on.” The authors go so far as to suggest that “Western kinship is distinctly and perhaps increasingly, female-oriented.” This is sort of an interesting assertion to make, given that this study includes arguably the most gender egalitarian country in the world (Sweden). The authors suggest that divorce and separation tend to weaken paternal relations far more than maternal ones, thereby exacerbating the matrilineal tilt. In other words, even if dads in Sweden are taking on a greater role in family life, heightened rates of family instability may ultimately undermine the gender balance of family life.

Regarding "redshirting everyone", I think one simple, positive way to frame such a move would be that it's effectively reversing the rigorization of Kindergarten, by which I mean the transformation from play-based to "achievement-focused" kindergarten that has mostly played out in my lifetime (sometime between 1992 and the present day).

My own eldest has had a very rough time making the transition from a play-based co-op preschool to the very rigid, "sit silently at a desk with 22 classmates completing worksheets all day, in between silently lining up by student ID number to proceed to/from 20 minutes of recess/lunch/gym" public kindergarten model in our neighborhood school.

The one (extremely important) difference between redshirting everyone and reverting to play-based kindergarten, is whether spending Age 5 in a playful, low-demand environment, is done on the public's dime in an elementary school, or on parents' dimes at home or in pre-K.

Great roundup. I've been following the "redshirting" discourse for a bit now, and so am really interested on the proposal that there are reasons to start school later for girls as well as boys. You've hit on the crux of the question I think in asking whether it's about the child's "readiness" for school in relation to their peers or in relation to the demands of school that makes the difference for them.

It seems notable and relevant to these debates that a society that is considered to be a model in childhood education, Finland, doesn't start students in school until they are 7!